An article caught my attention this week in The Australian about owners selling the air above their apartment blocks for profit.

Take a look:

‘Eight owners of a Sydney apartment block recently banded together to sell off the airspace above their building for almost $1m and the idea is catching on.

‘Rooftop property development specialist Warren Livesey estimates the airspace above strata unit blocks in Australia is an untapped $100bn plus market.

‘He has been selling Sydney strata rooftops and other unused space since 2008 through his business Buy Airspace and calls the deals a win-win for all parties…

‘He negotiated the deal for owners of the apartment block in Sydney’s east to sell roof space to a developer for about $900,000 subject to council approval.

‘A development application for a roof top apartment will soon be lodged with the local council and the sellers plan to use the funds to repair and upgrade their building and split the remainder between them.

‘For Mr Livesey, utilising airspace was an idea whose time has come.

‘“There are millions of people coming to Australia and we just don’t have the housing. Ultimately by utilising airspace we are creating additional development sites in and around existing infrastructure,” he said.’

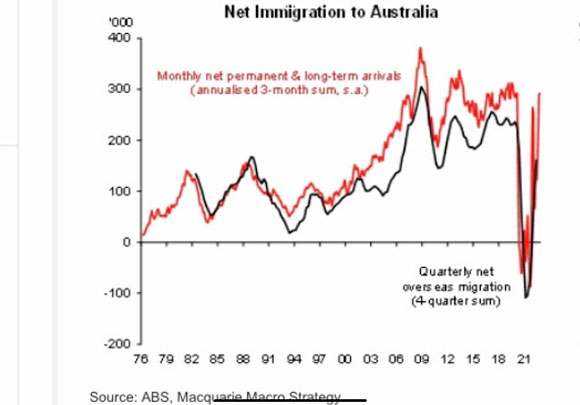

It’s true, immigration is rocketing toward record levels.

From economist Pete Wargent’s Daily Blog:

‘Looking through the seasonal noise of travellers and temporary residents, monthly net permanent and long-term immigration into Australia has already returned to pre-pandemic levels and will soon be breaking new highs.

‘Macquarie Macro with one of their favourite charts

|

|

‘Treasurer Chalmers conceded this week that net immigration in 2022-3 could top 300,000, well ahead of the assumptions keyed into Budget papers.

‘This would take total annual population growth to around record highs of about 450,000 this year.’

With vacancy rates at record lows and rents continuing to climb, housing pundits are screaming ‘we need more supply’.

|

|

| Source: Twitter |

Considering there’s an abundance of low- to mid-rise apartment blocks in the major capitals, utilising the space above them can certainly have its advantages.

Still, whilst it is a clever concept, it is not a new one.

The above scenario reminds me of a similar initiative in Israel called ‘Tama 38’.

It stands for ‘The National Outline Plan for the Strengthening and Development of Buildings in the Seismic Zone’.

Tama 38 allows for urban renewal by giving tenants in older blocks (pre-1981) the option to sell the air rights above their apartment building to developers.

In exchange for the sale of the air rights, the money is used to strengthen the structural integrity of the building to protect against earthquakes, as well as to upgrade the units (sometimes expanding them).

As Mr Livesey points out in the article above, it’s effectively a ‘win/win’.

The policy preserves the rights of tenants, but so too does the existing urban fabric without requiring blocks to be demolished and reconstructed.

The one issue in Israel, however, is that developers won’t purchase air rights unless there is profit to be made from the sale!

And in this region, the big money comes from overseas buyers, not the local population.

As a result, the blocks that are successful in securing the rights to sell for urban renewal tend to be in expensive neighbourhoods. Leaving poorer neighbourhoods with structures that still risk crumbling down if an earthquake hits, or without a bomb shelter in times of war. The policy cannot be successful when run on private interests alone. It needs government intervention to fund renewal where developers fear to tread.

All in all, whilst there are benefits, selling air rights under current policy is, in reality, just another land grab.

(Land in economics refers to all-natural elements that can be enclosed and traded for profit: land, water, the electromagnetic field, and air.)

In fact, the concept was first conceived not from building up, but building down.

In 1903, a smart engineer from New York named William Wilgus was working to rebuild the Grand Central Station and electrify the steam locomotives.

William’s light-bulb moment was moving the terminal underground. That idea was inconceivable under steam technology.

This way, said William, developers could ‘take wealth from the air’ (i.e: the ground above) and claim the space on ‘air rights’ for themselves.

The buildings above would sit on the steel and concrete roof that covered the tracks.

The sale and lease of those buildings would create enough wealth to finance the transport system below — a form of ‘value capture’.

It took 10 years, one million pounds of dynamite, and the removal of almost three million cubic yards of rock and soil before William’s plan came to fruition. However, his ingenuity transformed Manhattan’s landscape forever.

As mentioned above, nowadays, developers are more likely to buy the air rights above an existing building and ‘air bank’ it (when zoning permits) to advantage their development.

The best and most famous example is Donald Trump’s monument to himself, the Trump Tower.

It cost more than US$330 million to build. It’s one of the tallest residential concrete structures on Earth.

It was constructed using more than 90,000 tonnes of reinforced concrete:

|

|

| Source: BBC News |

It opened in the early ‘80s mid-cycle downturn, as you would expect based on the ‘skyscraper curse’ (opening the world’s tallest structures always happens during a recession or depression).

Inside is a waterfall and public garden encased in more than 200 tonnes of imported Italian marble.

The development would (and should) have made a spectacular loss.

However, Trump was smart enough to purchase the neighbouring block’s air rights.

That block was owned by the jeweller Tiffany & Co.

The conversation is recorded in Theodore Steinberg’s book Slide Mountain, or, The Folly of Owning Nature (1996):

‘I’m offering you five million dollars [a bargain at the time]…to let me preserve Tiffany. In return you’re selling me something—air rights—that you’d never use anyway.’

Tiffany’s air rights allowed Trump to boost the floor space in the building by 50%.

Building further outwards than would have been permitted otherwise.

This increased the price of each apartment substantially.

New, one-bedroom studios sold for half a million dollars upon completion (US$1.2 million in today’s terms).

Views were guaranteed for the life of the development.

Trump’s building changed the way developers looked at air rights. And it triggered the 1980s construction boom on a magnitude that had never been seen before.

Is this something we can expect to see in this current cycle?

The history is interesting. But the lesson here is clear.

To see these kinds of developments occurring is incredibly bullish for the cycle and hints at what awaits as we climb the ladder to the 18-year peak.

Onwards, and, dare I say, upwards to 2026.

Best wishes,

|

Catherine Cashmore,

Editor, Land Cycle Investor

Comments