In 1904, Elizabeth Magie patented a board game she created. She called it The Landlord’s Game.

The game pretty much mimicked real life. There was money, banks, deeds, jail…you could even make a wage.

Yep, you probably guessed it. Her game later turned into what we know today as Monopoly.

If you’ve ever played it, there are a few ways to make money.

You can get a ‘salary’ every time you go around the board.

Or you can have a stroke of luck. Through the chance cards, you may get money by winning the lottery or receiving an inheritance.

You could also invest your wages and savings into buying land and infrastructure and developing it by building homes and hotels. You can then charge rent to any other player that lands on your property. That’s, in fact, where the big bucks are.

Magie created the game to teach children the basics of our economic system.

As Magie herself noted in The Single Tax Review:

‘Children of nine or ten years and who possess average intelligence can easily understand the game and they get a good deal of hearty enjoyment out of it. They like to handle the make-believe money, deeds, etc., and the little landlords take a general delight in demanding the payment of their rent. They learn that the quickest way to accumulate wealth and gain power is to get all the land they can in the best localities and hold on to it.’

But as the game goes on, there is less money in the game, less property to buy, and a limited number of houses and hotels available to build.

The game also teaches about resource scarcity…

Things are tight in the commodity space

The war in Ukraine…supply chain disruptions…inflation…COVID.

With all these crises, resource shortages are worsening every day. We’ve seen a run-up in conventional energy commodity prices such as oil, gas, and coal.

But also, we could be facing shortages of critical materials needed for the energy transition.

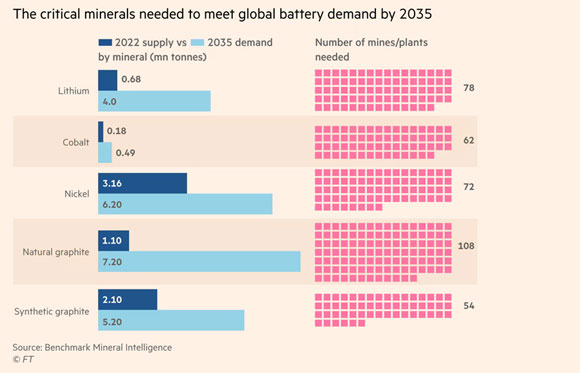

As electric vehicle demand continues to increase, we will also need to expand our supply and refinement of critical minerals such as lithium, graphite, nickel, and cobalt…by a lot.

Just to give you an idea, check out the chart below:

|

|

| Source: Financial Times |

But it’s not just for electric vehicles. Wind farms, solar farms, stationary batteries…you name it.

Demand for critical materials is set to soar as countries continue to move through the energy transition.

Yet as my colleague Kiryll Prakapenka pointed out yesterday, there’s been a lack of investment when it comes to new mining supply.

All that could lead to a growing disconnect between supply and demand. As Fatih Birol from the International Energy Agency put it last year (emphasis added):

‘The data shows a looming mismatch between the world’s strengthened climate ambitions and the availability of critical minerals that are essential to realising those ambitions.

‘Left unaddressed, these potential vulnerabilities could make global progress towards a clean energy future slower and more costly — and therefore hamper international efforts to tackle climate change. This is what energy security looks like in the 21st century.’

Indeed.

And with scarcity looming, competition for critical materials is intensifying.

The global race for critical minerals steps up a notch

Last week the Canadian government made quite a move.

It forced three Chinese companies to give up their investments in lithium companies over national security concerns.

It asked Sinomine Rare Metals Resources to abandon Power Metals Corp, Chengze Lithium International to sell Lithium Chile, and Zangge Mining Investment to leave Ultra Lithium Inc.

As Industry Minister Francois-Philippe Champagne said in a statement:

‘While Canada continues to welcome foreign direct investment, we will act decisively when investments threaten our national security and our critical minerals supply chains, both at home and abroad.’

You can see that countries are really getting serious about developing and protecting their local supply chains regarding critical materials.

Of course, it’s not just Canada.

As we mentioned last week, recent US legislation gives tax incentives to electric vehicles that hold critical minerals produced in the US or in countries that have free trade agreements with the US.

Japan is looking to mine rare earths in the Pacific Ocean at a depth of 6,000 metres, to break China’s dominance in this space.

Indonesia, the world’s largest nickel producer, is looking at the possibility of establishing an ‘OPEC-style’ structure for battery materials to have more control over supply and prices.

And Argentina, Bolivia, and Chile have been having similar chats when it comes to lithium supply and prices. The three countries make up the ‘lithium triangle’, which holds around 54% of the global lithium reserves.

In short, the geopolitics of energy is changing fast, and Australia is in a great position to take advantage of it.

Stay tuned for more on this tomorrow…

All the best,

|

Selva Freigedo,

For Money Morning

Selva is also the Editor of New Energy Investor, a newsletter that looks for opportunities in the energy transition. For information on how to subscribe, click here.