If you look at the run-up to the peak in the last few cycles — 1973, 1989, 2008 — rates always rose alongside prices (much like they’re doing now, as we approach the expected 2026 peak).

It required lending institutions to find innovative ways to attract borrowers into the winner’s curse phase of the cycle (the final two years), regardless of cost-of-living pressures.

Homer Hoyt noted this reoccurring pattern in the run-up to the peak in his book One Hundred Years of Land Values in Chicago (published in 1933).

Commenting on the excesses of the Roaring Twenties, he said:

‘…the point was reached in 1928 where 100 per cent loans were made on first mortgages in many cases, and where an additional 20 per cent was obtained on a second mortgage.

‘These junior issues had hitherto enabled an owner to raise 80 per cent of the conservative value of his property on the basis of mortgages.

‘A first mortgage of from 50 to 60 per cent of the value of improved holdings could be secured at normal interest rates, and an additional 20-30 per cent on a second mortgage at a premium of from 3 to 6 per cent additional per year.

‘In the inflated market of 1927 and 1928, however, the two mortgages frequently exceeded 100 percent of the cost value of the property even at boom levels.’

You’ll recall that the extension of 100%-plus loans was rife, leading to the subprime crash of 2008.

Prior to 2000, subprime lending had been virtually non-existent. In the second half of the cycle, however — post-2001 — it took off exponentially.

Looking back at the 1970s to early 1990s cycle, inflation rates and interest rates rose dramatically, laying the foundation for the ‘savings and loans crises’.

Savings and loan institutions grew a whopping four times the size of the banking industry in the run-up.

They used short-term deposits to fund long-term fixed-rate home mortgages (borrowing short to lend long), allowing thousands to enter the market.

But rapid inflation and rising short-term rates left many paying more to their depositors than they were making on their mortgages.

At the time, US President Ronald Reagan attempted to remedy the situation (kick the can down the road) in the second half of that cycle with deregulation (the Garn-St Germain Depository Institutions Act).

The new laws allowed savings and loan institutions to invest in risky real estate projects, regardless of location.

Loan-to-value ratios, previously limited to 75%, rose to 100% in the years leading to the peak.

Notably, the reforms were coupled with a tax stimulus package: Reaganomics. Sold as a way to ‘boost’ the economy, it inevitably ‘trickled down’ directly into land prices.

Similar trends will no doubt feature in the run-up to the peak of this cycle.

It’s already occurring globally.

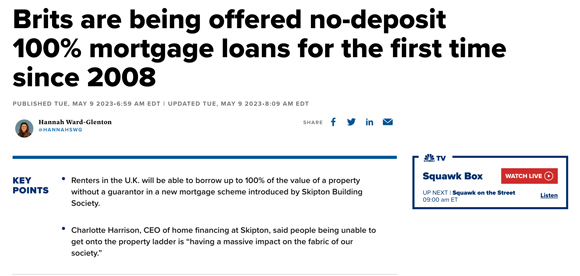

You may have already caught wind that banks are gearing up in the UK to offer no-deposit 100% mortgage loans.

| |

| Source: CNBC |

‘The new mortgage product, aimed at first-time buyers who are currently renting, has a fixed rate of 5.49% for five years, over a maximum term of 35 years.

‘The average five-year rate was 5% in March, according to the Moneyfacts UK Mortgage Trends Treasury Report, across all loan-to-value ratios. Buyers typically get a 5.33% mortgage rate on 95% LTVs, according to the report…’

CNBC

Then, of course, there’s the new trend for ‘ultra-long’ mortgages being promoted as a creative way to get into the property market.

From the UK Financial Mail:

‘Soaring numbers of homebuyers are taking out ultra-long mortgages that slash their monthly payments – but will cost them tens of thousands of pounds in extra interest over the long term.

‘Nearly one in five first-time buyers now take out mortgages with terms of 35 years or longer, up from one in ten a year ago, according to banking trade body UK Finance.

‘The number of people taking out 30 to 35-year mortgages has also jumped from 34 per cent to 38 per cent during that time. Until recently, mortgage terms were rarely longer than 25 years.’

It’s no wonder that Rightmove, the UK property portal, has reported that the average asking price of properties popular with first-time buyers — those with one or two bedrooms — has hit a record price of more than £224,963.

It’s 2% higher than a year ago, even though higher mortgage rates have been biting into budgets.

It’s all so predictable — if you know the cycle.

As Fred Harrison tweeted a few weeks ago…

| |

| Source: Twitter |

Similar reforms allowing more buyers to enter the market are also happening here.

Despite the latest 0.25% rise in the cash rate, several lenders have implemented various policy modifications to aid borrowers.

Resimac, a non-bank lender, has decreased its serviceability assessment buffer to 2% across all its products.

Westpac — along with its subsidiaries St George, Bank of Melbourne, and BankSA — has also introduced a provision where certain borrowers looking to refinance their home loans are able to undergo a ‘modified Serviceability Assessment Rate’ if they don’t meet the criteria of the standard test.

Other banks are allowing overtime pay and allowances on applications for loans (income that’s not previously been accepted for assessment).

Queensland-based banking and insurance provider RACQ introduced 40-year terms on select home loans last year.

And earlier this year, UBank announced it is extending its loan term for refinances from 30 to 35 years.

The bottom line here is that banks must continue to attract borrowers — and as the cycle progresses, they’ll inevitably continue to find creative ways to do so.

As we enter the winner’s curse phase of this cycle, stage three tax cuts will take effect — creating a flat rate of 30% for those making between $45,000–200,000.

Along with the rise of super to 12% of wages into 2025/26, it’s going to encourage more money into markets at precisely the wrong time.

Subscribers already know what comes next.

A crash into 2028…

If you want to know how to trade the markets to take advantage of the boom, and hedge against the bust, consider signing up for Cycles, Trends & Forecasts today.

Best Wishes,

|

Catherine Cashmore,

Editor, Land Cycle Investor