The yield curve is a remarkably simple construct with predictive properties that are equally remarkable. Constructing a yield curve begins with a graph consisting of a vertical y-axis showing interest rates and a horizontal x-axis showing the maturity of the instruments under consideration.

In today’s low-rate environment, a y-axis that ranges from 0% at the intersection with the x-axis up to 5% at the top of the y-axis works just fine. Of course, in other historical periods, the y-axis would have to go as high as 25% to accommodate the available data. It’s also possible for the y-axis to dip to less than 0% in markets where negative yields to maturity exist as they do in some markets today.

The x-axis begins with zero at the intersection with the y-axis and then progresses through time as you move from left to right. The points on the x-axis might be one month (as is the case of one-month Treasury bills), then two years, five years, seven years, 10 years, 20 years, and 30 years as you move to the right. There are some 100-year bonds out there, but they are rare and thinly traded. The 30-year mark (which is the longest maturity US Treasury bond outstanding) does fine for our purposes.

It’s important to note that there’s no such thing as a generic yield curve. There are as many different yield curves as there are fixed-income markets. The yield curve for the US Treasury market is more or less the layout described above.

There are quite different yield curves for other sovereign bond markets, corporate bonds, junk bonds, municipal bonds, etc. Mixing municipal bond data and Treasury bond data on the same yield curve doesn’t tell us much and muddies the waters in terms of predictive analytic value.

There’s nothing wrong with putting two different yield curves on the same graph in order to make a comparison based on different dates or different markets or to illustrate spreads, but it makes no sense to blend data from disparate markets into a single curve.

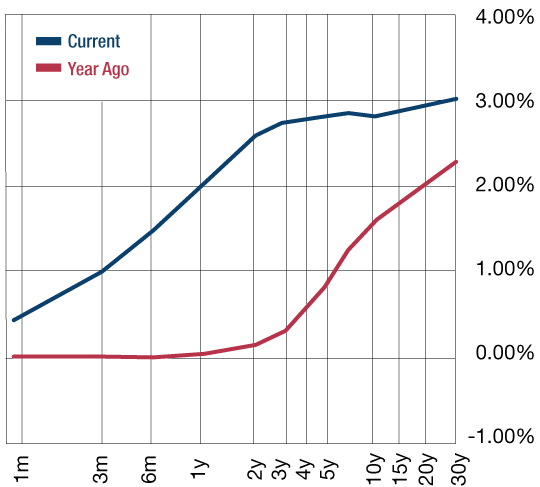

It’s also important to note that different scales will be needed for different yield curves. If we’re graphing the US Treasury market as in the curve presented below, a range of -1–4% captures all outstanding maturities. If you were presenting the junk bond market, the y-axis would have to extend as high as 15% to capture yields on most outstanding issues.

The current yield curve for the US Treasury market is presented below. The y-axis (right-hand scale) runs from -1–4%, and the x-axis runs from a one-month Treasury bill to the 30-year Treasury bond. The blue line is the current yield curve, and the red line represents the yield curve one year ago:

|

|

| Source: Self |

The interest rates represented on the right-hand scale are calculated as the yield-to-maturity (YTM) expressed as a percentage return on the instrument based on market prices as of the date of calculation. The YTM is different from the coupon that the note actually pays, which was set at the time it was first sold at auction. That’s because Treasury notes are traded continually in liquid markets. Prices go up or down on a minute-by-minute basis.

Here’s the basic bond maths. Coupons are set on the auction date. As bond prices go up, the YTM goes down and vice versa. So a bond with a par value of $100,000 might pay a coupon of 2.5% when sold at auction. However, if that bond later sells for $101,000, the YTM will drop to less than 2.5% because the buyer only gets $100,000 at maturity.

The $1,000 premium is lost over time. Likewise, if that same bond later sells for $99,000, the YTM rises to more than 2.5% because the buyer picks up an extra $1,000 at maturity. The coupon stays the same, but the YTM goes up or down inversely to the price of the note in secondary market trading.

What this means is that yield curves are shape-shifting. They can steepen, flatten, or even invert (explained below) based on different prices paid for different securities at different times. And that’s where the predictive analytic power of yield curves comes into play.

The shape shifting is not random. It’s the result of real investors making bets with real money. The yield curve is like a snapshot (or even a movie over time) of how investors view the prospects for interest rates and the economy both now and in the future.

The yield curve is the distilled wisdom of all the big money players in the world, from sovereign wealth funds to hedge funds to major banks and institutional investors. Bond investors have a much better track record than stock investors when it comes to seeing the future. And if you want to know what bond investors are thinking, just look at the yield curve. The trick is how to interpret what you see.

Here’s how to interpret the yield curve

The yield curve is what analysts call information rich. This means that the information presented in the yield curve goes far beyond the superficial presentation of maturities and yields. The shape of the yield curve tells you more, and the shape-shifting over time (comparing yield curves created on two different dates) tells you even more.

Particular slopes in different parts of the curve — short term, intermediate term, or long term — are highly revealing as are comparisons of slopes at different maturities and so on. This is how pros look at the yield curve. It’s not difficult; you can easily do it too.

Before jumping into detailed analysis, it’s useful to have a baseline. What’s a normal yield curve? Yield curves are normally upward sloping from left to right. This means that investors demand higher rates at longer maturities. This makes sense.

In a world without inflation, recession, volatility, war, etc., there are no exogenous factors to bend or shape the curve. Investors simply want to get paid for increased risk of unexpected developments at longer maturities. This is called risk premium. So a normal yield curve might show 0.5% at the one-month point, 1.5% at the two-year point, and 2% at the 10-year point. That reflects a normal risk premium and is mildly upward sloping from left to right.

Of course, the world today bears no resemblance to the normal world just described. Inflation, recession, volatility, and war are all front and centre. How the yield curve is shaped by these factors (and, more importantly, what the yield curve tells us about how these factors will evolve) is why yield curve analysis is so valuable.

Keep an eye out next Wednesday for the fourth and final instalment of this series of articles.

All the best,

|

Jim Rickards,

Strategist, The Daily Reckoning Australia

This content was originally published by Jim Rickards’ Strategic Intelligence Australia, a financial advisory newsletter designed to help you protect your wealth and potentially profit from unseen world events. Learn more here.