Petrodollars are balance-of-payments surpluses of countries that export oil, which is then invested abroad in securities denominated in US dollars.

That is a technical and difficult definition, so this guide aims to unpack exactly what the petrodollar is, how it came about, what it signifies, and what its outlook is.

Navigate to a section quickly:

-

- What is a petrodollar?

- Bretton Woods, gold, and the US dollar

- Petrodollars and the 1973 oil crisis

- The petrodollar is born

- Petrodollar recycling

- Do oil-exporting countries only accept US dollars?

- Will the petrodollar system collapse?

- Will Russia destabilise the petrodollar system?

- Could Bitcoin replace the petrodollar system?

What is a petrodollar?

The US dollar is the most commonly used currency for buying all types of resources and assets globally.

Including oil.

At the moment, oil is experiencing the highest demand among fossil fuels and other natural commodities because of its wide range of uses across all industry sectors.

And almost all oil sold worldwide is in US dollars.

When newspapers report on the gyrations of the oil price, the commodity is always priced in USD.

So the term petrodollar refers to the US dollars an oil-exporting country receives for the oil it sells.

Although it sounds like a regular sale of goods where both sides win, it can be a bit more complicated than that.

But first, a bit of history…

Bretton Woods, gold, and the US dollar

The history of the petrodollar is heavily tied to geopolitics, especially the geopolitics of the US and its role as the world’s reserve currency.

So to understand the petrodollar system, we need to go as far back as the Bretton Woods Conference held in New Hampshire in 1944.

Delegates to the conference from 44 nations agreed to establish the International Monetary Fund and what became the World Bank Group.

They also created a new international monetary system known as the Bretton Woods system.

The Bretton Woods system involved pegged exchange rates and lasted until 1971, superseded by a system of floating exchange rates.

As Gregory Mankiw explained in his best-selling macroeconomics textbook:

‘Under a system of fixed exchange rates, a central bank stands ready to buy or sell the domestic currency for foreign currencies at a predetermined price. For example, suppose the Fed announced that it was going to fix the yen/dollar exchange rate at 100 yen per dollar. It would then stand ready to give $1 in exchange for 100 yen or to give 100 yen in exchange for $1. To carry out this policy, the Fed would need a reserve of dollars (which it can print) and a reserve of yen (which it must have purchased previously).’

In 1958, the Bretton Woods system became fully operational, and world currencies became convertible.

That meant that countries settled international balances in US dollars, and, in turn, US dollars were convertible to gold at a fixed exchange rate of US$35 an ounce.

As the reserve currency, it was the US’s duty to keep the price of gold fixed and to adjust the supply of US dollars to maintain the system’s confidence in gold’s faithful convertibility.

As Greg Ip summed up in his The Little Book of Economics:

‘Participating countries fixed their currencies to the dollar and the United States fixed its dollar to gold; it would convert another country’s dollars to gold at $35 per ounce. The International Monetary Fund would police the system, lending money to a country that struggled to finance a current account deficit, and permitting it to devalue if necessary to eliminate the deficit altogether.’

Dollars, backed by a promise to pay in gold, became the primary method of trade for worldwide settlement.

The US grew into the world’s largest lender and economic superpower.

But the system didn’t last. In fact, it fell apart.

Beginning in the 1960s, the US began to run current account deficits.

A current account deficit is an excess of expenditure over receipts in a country’s balance of payments.

With the US running current account deficits in the 1960s, other countries began holding a lot of US dollars.

Eventually, the world cottoned on that the US probably didn’t have enough gold to redeem those dollars.

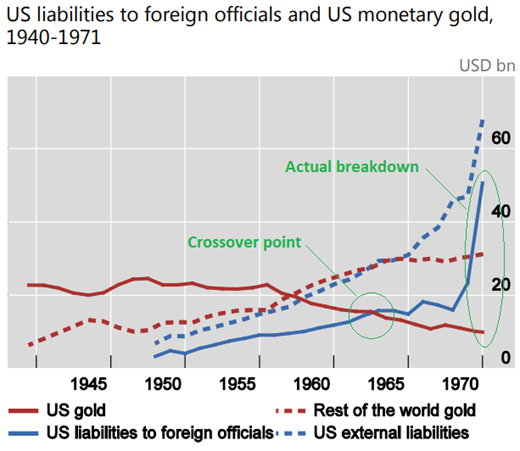

Source: Lyn Alden

As investment strategist Lyn Alden explains:

‘By the late-1950s, US external liabilities exceeded US gold reserves. By the mid-1960s, the subset of US external liabilities that were owed to foreign officials exceeded US gold reserves, which was the true crossover point where the system became troubled. And by 1971, the system broke down and was defaulted on by the United States.’

To pre-empt a crisis, then US President Richard Nixon famously ‘shut the gold window’, declaring that the US would stop exchanging its gold for dollars.

The international monetary system was now largely based on floating exchange rates, and the Bretton Woods system was no more.

Petrodollars and the 1973 oil crisis

But the collapse of the Bretton Woods system was not the only thing affecting the global economy and the US in particular.

A few years after the US abandoned the gold standard, it faced another problem: rising inflation.

The US’s earlier economic growth and low unemployment began to strain its productive capacity. Inflation rose and so did interest rates.

And then came the great oil crisis of 1973 in the form of the Arab oil embargo.

The 1973 oil crisis began in October of that year.

The crisis erupted when Saudi Arabia and other members of the OPEC (Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries) banned oil exports to countries that backed Israel during the Yom Kippur War.

Canada, Japan, the Netherlands, the UK, and the US were the first countries to be affected by the embargo.

The oil price had increased roughly 400% by the end of the ban in March 1974.

Before the oil crisis, oil was valued at around US$3 per barrel. However, the price skyrocketed to nearly US$12 per barrel towards the end.

A second major oil shock between 1979 and 1980 pushed oil prices from US$14 a barrel in 1978 to US$37.20 a barrel in 1980.

The petrodollar is born

In July 1974, Nixon sent US Treasury Secretary William Simon and his deputy, Gerry Parsky, on a secret mission to Saudi Arabia to work out the details of what became the petrodollar.

Operating in close coordination with US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, Simon spent four days in Jeddah, a city on Saudi Arabia’s Red Sea coastline, meeting with Saudi counterparts.

The stakes couldn’t have been higher. The future of the US dollar, the health of the US economy, and the replacement of US influence with Soviet influence in the Middle East were all at risk.

The deal that Simon offered was straightforward.

The Saudis would agree to price oil in dollars, and to reinvest those dollars in US Treasury securities and Eurodollar deposits in US banks. (Eurodollars, by the way, simply refers to US dollars held by banks outside of the US.)

In exchange, the US would take steps to stabilise the exchange value of the US dollar and agree to sell advanced weapons to the Kingdom.

The final twist was that US banks would ‘recycle’ the petrodollars as loans to emerging markets in Latin America, South Asia, and Africa.

In turn, those countries would purchase US, European, and Japanese exports. That would reignite global growth and increase the demand for oil.

It was the ultimate win-win.

The Saudis got weapons, safe investments, high oil prices, and increased demand for its oil.

The US got debt financing, weapons sales, increased Middle East influence, and a dominant role for the US dollar in international reserve positions.

Once oil was priced in US dollars, every country in the world would need greenbacks because they all needed oil.

Source: Bloomberg

Lyn Alden summed up the system well

‘With the petrodollar system, Saudi Arabia (and other countries in OPEC) sell their oil exclusively in dollars in exchange for US protection and cooperation.

‘Even if France wants to buy oil from Saudi Arabia, for example, they do so in dollars. Any country that wants oil, needs to be able to get dollars to pay for it, either by earning them or exchanging their currency for them.

‘So, non oil-producing countries also sell many of their exports in dollars, even though the dollar is completely fiat foreign paper, so that they can get dollars for which to buy oil from oil-producing countries. And, all of these countries store excess dollars as foreign-exchange reserves, which they mostly put into US Treasuries to earn some interest.

‘The petrodollar system is creative, because it was one of the few ways to make everyone in the world accept foreign paper for tangible goods and services. Oil producers get protection and order in exchange for pricing their oil in dollars and putting their reserves into Treasuries, and non-oil producers need oil, and thus need dollars so they can get that oil.’

Initially, the petrodollar deal worked well.

In the five months after the deal was finalised, the US dollar rallied 4.6%. The dollar declined only slightly through the end of 1976 but began a precipitous decline in 1977.

By October 1978, the US dollar Index had fallen nearly 13% from the 1975 high.

Saudi Arabia saw this rapid decline of the US dollar as a breach of the petrodollar deal. It retaliated by doubling the price of oil between April 1979 and April 1980.

Once again, the US economy dipped into recession, and Americans waited in long lines to get gasoline. The petrodollar deal seemed to be coming apart at the seams after only four years.

By now, Jimmy Carter was president and Kissinger and Simon had left government to pursue private careers.

Still, the petrodollar deal was too important to the Saudis and the US to fall by the wayside. President Carter saved the day by appointing Paul Volcker as Chairman of the Federal Reserve in August 1979.

Volcker immediately set out to save the dollar by raising interest rates from 11% when he took office to a high of 19% in 1981. It was tough medicine for the US economy, but it worked.

Inflation plunged from 15% in 1980 to 4% by the end of 1982. The Fed’s US Dollar Index soared from 84.13 in October 1978 to 92.48 in November 1980, about where it was when the petrodollar deal began.

What happened next secured the success of the petrodollar deal for the next 30 years.

Volcker’s tight money policy, combined with Ronald Reagan’s low taxes and reduced regulation, sent the US economy and the US dollar on a tear. By March 1985, the dollar index reached an all-time high of 128.44, a spectacular 53% gain from the October 1978 low.

This period of the 1980s was the heyday of ‘King Dollar’.

Petrodollar recycling

A technical but important concept to understand when it comes to petrodollars is petrodollar recycling.

Petrodollar recycling refers to the petrodollars oil-exporting countries send back — or recycle — to oil-importing countries to boost the latter’s economic growth.

Higher oil prices reduce the purchasing power inside oil-importing countries, curtailing their economic growth.

But when oil-exporting countries use revenue from their oil sales and purchase goods or bonds from oil-importing countries, the curtailing effects on economic growth are mitigated.

That, in a nutshell, is petrodollar recycling.

Interestingly, one of the primary petrodollar recycling methods in the 1970s was through arms sales.

Do oil-exporting countries only accept US dollars?

Before OPEC countries demanded US dollars for their oil, about 20% of the world’s oil had been sold for British pounds.

When US dollars became the universal oil currency, that number fell to less than 6%.

The euro has also featured as an important oil-trading currency.

Saddam Hussein, ex-ruler of Iraq, attempted to destabilise the petrodollar system.

In 1999, Hussein announced that Iraq would start selling oil for euros instead of dollars. By February 2003, he had sold 3.3 billion barrels of oil for €26 billion.

For a moment, it seemed like the world could switch to the petroeuro.

As Geoffrey Heard wrote for the Global Policy Forum:

‘In 1999, Iraq, with the world’s second largest oil reserves, switched to trading its oil in euros. American analysts fell about laughing; Iraq had just made a mistake that was going to beggar the nation. But two years on, alarm bells were sounding; the euro was rising against the dollar, Iraq had given itself a huge economic free kick by switching.

‘Iran started thinking about switching too; Venezuela, the 4th largest oil producer, began looking at it and has been cutting out the dollar by bartering oil with several nations including America’s bete noir, Cuba. Russia is seeking to ramp up oil production with Europe (trading in euros) an obvious market.

‘The greenback’s grip on oil trading and consequently on world trade in general, was under serious threat. If America did not stamp on this immediately, this economic brushfire could rapidly be fanned into a wildfire capable of consuming the US’s economy and its dominance of world trade.’

In March 2003, a US-led coalition invaded Iraq.

Hussein was removed from power, and by June 2003, Iraq had returned to selling oil in US dollars.

Will the petrodollar system collapse?

A big question in the world of geopolitics and international economics is whether the US dollar’s hegemony as an oil-trading currency will wane.

Already there is talk of the petroeuro and the petroyuan as Europe and China grow in power and influence.

In March 2022, for instance, The Wall Street Journal reported that Saudi Arabia was contemplating pricing some of its oil sales to China in yuan.

China already buys more than 25% of Saudi Arabia’s oil exports. So, if those sales are priced in yuan, the demand for China’s currency will rise while demand for the US dollar will fall.

But why should we care about a potential petrodollar collapse?

Considering that the world consumes more than US$2 trillion worth of crude oil a year, there’s a significant correlation between petrodollars and the value of US dollars.

It’s hard to predict what the global economic consequences would be if countries began buying oil with alternative currencies and thus reducing demand for the greenback.

The Federal Reserve Bank of New York warned that petrodollar recycling has the tendency to inflate the US’s debt obligations even when it boosts consumption:

‘The recycling of petrodollars into the U.S. financial markets has supported activity here by allowing for higher consumption and investment spending than otherwise would have occurred. The concomitant cost has been a further expansion of the U.S. economy’s already sizable net international liabilities.’

Growing debt is unsustainable and can jeopardise the US’s economic health.

Another consideration is that the US is no longer as dependent on Saudi Arabia for energy supplies.

It has become a net exporter of energy and has the largest oil reserves in the world.

All the conditions that gave rise to the petrodollar now stand in the exact opposite position of where they were in 1975.

Neither the US nor Saudi Arabia has much leverage over the other, in contrast to 1975 when each side held powerful trump cards.

This doesn’t mean that oil will be priced in a currency other than US dollars tomorrow. It means that a new pricing mechanism is possible, and no one should be surprised if it happens.

Saudi Arabia could easily price oil in yuan, swap the yuan for Swiss francs or SDRs (Special Drawing Rights) and use the proceeds to add to its reserves or buy gold.

Saudi Arabia could also price oil in SDRs or gold and hold those assets or swap them for other hard currencies to diversify away from dollars. The possibilities are numerous.

For some thinkers, like Fat Tail Investment Research’s Jim Rickards, the conversion of oil prices away from US dollars to some alternative is just a matter of time.

In their view, as momentum toward these alternatives grow, the role of US dollars as a reserve currency could diminish quite quickly — like the sterling’s role between 1914 and 1944.

Macroeconomic trends are notoriously hard to foretell but one thing is true — nothing lasts forever.

The US dollar supremacy in pricing oil is not inherently destined to prevail indefinitely.

But time will tell.

Will Russia destabilise the petrodollar system?

Before we answer that question, let’s explore what the SWIFT system is and how it is used.

SWIFT is a messaging system used by banks and financial institutions worldwide. SWIFT stands for the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication. It is headquartered in Belgium and connects more than 11,000 banks in more than 200 countries.

SWIFT is a messaging platform, not a payment system. It allows banks that are members of the SWIFT network to transfer money quickly and securely worldwide.

After Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, Russian banks were subsequently banned from the SWIFT network. This means that it’s now a lot harder for Russia to buy and sell dollars in exchange for their oil.

But Russia might as well have an ace up its sleeve; it’s China’s second-largest oil supplier, selling them approximately one million barrels of oil every day.

China has its own bank communication service called CIPS (Cross-Border Interbank Payment System), which launched in 2015. It has a network of more than 3,000 banks in more than 167 countries. Now that China is looking to buy oil from Saudi Arabia with yuan instead of dollars, why wouldn’t they pay for Russian oil with yuan, too?

If Russia and Saudi Arabia agree to sell their oil to China for yuan instead of US dollars, this might impact the petrodollar system. The dollar’s value could also be affected once its demand decreases.

Could Bitcoin replace the petrodollar system?

In 2020, the Journal of Institutional Economics published a study exploring four potential monetary outcomes for the world economy.

One outcome is where the US dollar hegemony endures.

Another is where the world divides into competing monetary blocs (think the EU, China, and the US).

A third outcome is the establishing of an international monetary federation.

A final outcome envisages a world of total monetary anarchy.

Of course, the options are not exhaustive. And some cryptocurrency advocates think there is a fifth option — Bitcoin [BTC] becomes the global reserve asset.

One such advocate is Alex Goldstein.

Writing for Bitcoin Magazine, Goldstein argued that bitcoin could supplant the US dollar as the de facto reserve currency of the world.

That would include the dismantling of the petrodollar system:

‘Born at a time when the previous world reserve currency had reached its apex, Bitcoin could introduce a new model, with more possibilities but also more restraint. Anyone with an internet connection will be able to protect their wages and savings, but governments, unable to so easily create money on a whim, will not be able to wage forever wars and build massive surveillance states that contradict the wishes of their citizens. There could be a closer alignment between the rulers and the ruled.

‘The big fear, of course, is that America will not be able to finance its exorbitant social programs and military spending if there is less global demand for the dollar. If people prefer the euro or yuan or bonds from other countries, the U.S. in its current form would be in big trouble. Nixon and Kissinger designed the petrodollar so that the U.S. could benefit from global demand for dollars tied to oil. The question is, why can’t there be a global demand for dollars tied to bitcoin?’

Summary

However, whether it be the yuan, euro, or bitcoin, it’s unlikely the petrodollar system will be superseded any time soon.

The US dollar is still the most dominant currency for pricing oil.

That said, the rise of China and the importance of the euro in international trade — as well as the emergence of cryptocurrencies — means the US dollar hegemony isn’t as pronounced as it once was.

And therefore, alternatives to the petrodollar system are easier to envisage now than ever before.