The core to learning the mechanics of the 18.6-year land cycle is fully understanding the role of economic rent (unearned income) and rent-seeking in the economy.

This is the ‘free lunch’ that so many desire — and the rights to which are protected by the elite at all costs.

Throughout the cycle, the greatest economic gains always come from owning the rights to land.

However, rent-seeking can take on many forms.

Cast your minds back to the taxi licencing monopoly, for example.

It was more profitable to hold a licence than it was to run a taxi company!

When Uber and Lyft entered the ridesharing industry around 2012–14, they were repeatedly stifled globally by government intervention.

Taxi drivers from London to Berlin staged mass protests. An estimated 30,000 London cabbies parked their cars, shut off meters, and blockaded streets!

However, just like land, the rental value of taxi fares went directly to the owners of the plates.

Not the drivers.

The drivers were left paying the licence holder an exorbitant share of their fares — often more than 50%!

Little was left over. The drivers were poor.

With the onset of Uber, consumers benefitted from lower fares and increased competition that ushered in better services.

However, Uber was not designed to give the drivers a greater advantage.

It’s not a worker-owned cooperative.

The company kept its fares unreasonably low to increase the number of users.

Drivers still struggle to make a profit.

Uber is now what we call a ‘platform monopoly’.

With this in mind, remember ‘land’ in economics refers to all-natural elements — including the electromagnetic spectrum upon which these platform monopolies are constructed.

Uber’s drivers use their own capital and labour to provide the profits needed for research into Uber’s future vision.

That of self-driving cars!

And like Facebook, Amazon, and Google, it’s not easy to attract the market away from the dominant platforms once they become established.

Take Google.

Long before Google (as we know it now) existed, Yahoo! was the premier internet search engine.

In 2002, Yahoo! tried to acquire its closest competitor for US$3 billion.

Google turned down the deal, saying it wanted at least US$5 billion.

Later that year, Google News launched — breaking new ground.

Google now controls 70% of the search-related advertising market.

Despite censorship pushing people onto other platforms, it has no viable rival…yet.

Right now, Alphabet Inc [NASDAQ:GOOGL] (Google) has a market cap of US$1.329 trillion.

Yahoo!, on the other hand, sold to Verizon in 2017 for, ironically, just under US$5 billion.

Governments will never intervene to collect the monopoly rents these platform monopolies create.

If they did, it would greatly assist competition in the tech sphere.

Instead, the preference is to strengthen them further with regulatory reform — giving the impression that they are somehow ‘safe’ spaces to work within.

|

|

| Source: MIT Technology Review |

Ironically, monopolist Rupert Murdoch coined it best in his 1994 John Bonython Lecture ‘The Century of Networking’, saying:

‘Because capitalists are always trying to stab each other in the back, free markets do not lead to monopolies.

‘Monopolies can only exist when governments protect them.’

It’s important you understand this.

Nature’s free lunch is why the 18.6-year cycle exists, why it repeats, and why it gives gravity to every other cycle in both stocks and commodities.

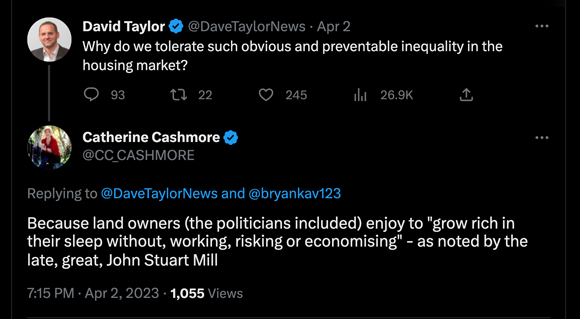

It’s also why the housing market is riddled with inequalities.

|

|

| Source: Twitter |

The key here is to be a rentier, not a renter! And speculate within the upward phases of the cycle accordingly.

To do this, you need to be aware of how technology impacts land prices and the cycle.

It formed the base of Henry George’s 1879 magnum opus, Progress and Poverty: an inquiry into the cause of industrial depressions and of increase of want with increase of wealth.

George wanted to know why, as economies progress, does poverty increase?

Why doesn’t the opposite happen?

Technology is exponentially deflationary. It gives us more for less.

So why doesn’t technology provide us with more time for leisure and less of a need to work and toil?

The answer, of course, is that land prices absorb the economic gains of all new innovations.

The profits are collected by the landlords, not the labourers.

Fred Harrison calls this the ‘Law of Absorption’.

As land prices increase, the split between the haves and have-nots broadens further.

It’s something completely missed in the mainstream — it’s never mentioned.

The large economic institutions (taking bets only a few weeks ago on when house prices would tank 15–30% based on hikes in the cash rate) simply cannot see the counter-trends in the bigger picture.

There are many examples I can use to demonstrate.

Take Amazon.

It was an early adopter of warehouse robotics when it purchased Kiva Systems in 2012 for US$775 million.

That allowed the company’s fulfilment centres to produce a higher revenue per square metre.

‘Amazon ready to unleash robot army in vast $500m warehouse.

‘… the southern hemisphere’s first Amazon robotics fulfilment centre … will be Australia’s largest warehouse with a footprint equal in area to 24 rugby league fields…

‘The $500 million project spanning 200,000 square metres in western Sydney’s Kemps Creek will double the e-commerce giant’s warehouse space when it opens early next year and create more than 1500 local jobs for people to work alongside advanced robots…

‘Hundreds of blue-and-grey robots will nip under the storage pods to select the mostly smaller items sold on amazon.com.au such as jewellery, books, electronics, pantry items and toys, and deliver them to the human workers in the despatch centre to be packed for delivery.

‘Craig Fuller, Amazon Australia director of operations, said the design does away with the need for aisles, allowing more inventory to be squeezed into the warehouse…

‘The facility…will allow the company to service 85 per cent of customers from one location…

‘One of Amazon’s key pillars is always trying to get faster and faster…’

The technology lowered the costs for Amazon.

But it also increases the value of their property.

Once innovations (such as the use of robotics in distribution or other AI systems that reduce the need for labour) are mass-produced and widely adopted, the prime commercial/industrial land sites will have already priced in the gains.

The adoption of technological innovation is also one reason why Warren Ebert (CEO of Sentinel Property Group) recently commented in an email to my colleague Callum Newman that ‘it’s never been easier to make money.’

The Australian-based property investment firm specialising in acquiring, managing, and developing commercial and industrial real estate is investing big in renewable energy, installing solar power systems across much of its property portfolio.

With power bills rising some 30% in some regions of Australia, that’s a smart move!

But where will the gains go?

To the landowners, of course.

As Warren said, ‘We will spend circa $4.4m on installation which will save us $1.5m year one. If capitalised that income it adds circa $20m to the value of the property.’

(Look out for more from Warren in future updates.)

For now, the lesson is clear.

Despite the deflationary trend of technological innovation, the cycle must continue to turn.

Land prices will absorb the gains of innovation up to the peak around 2026, whilst government legislation allows it.

And, from Warren again, ‘if you know how to stay ahead of the curve and invest in the right areas — It’s never been easier to make money.’

Sincerely,

|

Catherine Cashmore,

Editor, Land Cycle Investor

PS: Due to the Easter Weekend, we will not be publishing a Land Cycle Investor edition on Friday, 7 April. We will be back to normal publishing schedule next week.

![phabet Inc [NASDAQ:GOOGL] (Google) has a market cap of US$1.329 trillion](https://daily.fattail.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/LCI20230405_1_580.jpg)

Comments