The mainstream media (MSM) is full of stories of desperate families unable to secure rental accommodation.

Take this one from QLD:

‘Renee and Troy have been frantically flicking through real estate sites trying to find a rental after the owner of their old home gave them a 60-day vacation notice…

‘They are unable to put a number on how many applications have come back unsuccessful.

‘“We’ve lost count, but I would say well over 60 by now,” Troy said.

‘The rejection is taking a toll.

‘“It felt like we were being erased from the world. I just felt like we were nothing,” Renee said.

‘“I’m so lost right now that I don’t know how to keep going but I have two beautiful girls to think about at the end of the day and that keeps us going.”’

The situation is feeding into old arguments from the property lobby once again — that the reason we have high prices in Australia is simply a ‘lackof supply’.

Take this recent Sky News interview with Mark Bouris, Executive Chair of Yellow Brick Road Home Loans.

‘“How come I can’t rent a place”; Well you can’t rent a place because property supply is not there. “Who’s in charge of property supply, developers love to supply the market”; I’ll tell you who it is, it’s the government — either local, state and to some extent federal too.’

The thing is, what seems to be a shortage, with pressure coming from the property lobby to ‘increase supply now’, ignores one vital fact…

We have plenty of supply.

There are tens of thousands of properties sitting vacant.

The problem is, they’re not for sale or rent.

A few months ago, QLD authorities followed our lead over at Prosper Australia and used water data as a proxy to identify these vacant dwellings.

They uncovered a whopping 19,500 homes across lower Southeast Queensland that have water connected, but usage is so low that it seems no one’s been living there for months!

When the 2021 Census data was released, it produced a lot of hoo-ha in the media when it was uncovered that 9.6% of Australian properties were vacant on census night — during a pandemic that required most people to stay in place.

And while it’s not a perfect or long-term measure, it still applies to an eye-boggling 1,043,776 homes!

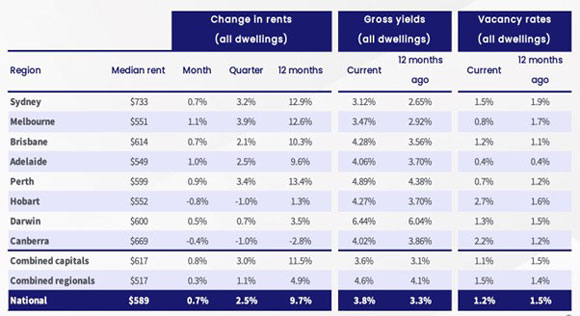

The latest rental data from CoreLogic shows Melbourne’s vacancy rate has dropped from 1.7% a year ago to just 0.8%.

|

|

| Source: CoreLogic |

However, once again, short-term vacancy statistics don’t expose the real issue.

We’ve been conducting studies into long-term vacant dwellings using water data as a proxy across the greater metropolitan area of Melbourne for more than 10 years at Prosper Australia.

We call them the Speculative Vacancy reports — report number 11 is due to be released soon.

You can peruse through some of the older editions here.

Consistently, the number of properties with water consumption so low it can be assumed no one is home equates to tens of thousands.

At its peak, the reports identified a potential 80,000 dwellings sitting vacant for 12 months or more.

Having penned a few of the Speculative Vacancy reports myself, I can tell you that historically, these long-term vacancies will sit hidden from view until a crisis hits.

The number of ‘speculative vacancies’ rises in the bull phases of the property cycle.

This is when capital gains are accelerating, and yields are being squashed as a consequence.

Owners may have a plethora of reasons to hold their homes vacant.

But while prices are rising, let’s face it, there’s an extra incentive to chase capital gains over rental yields and avoid dealing with long-term tenancy issues and potentially expensive changes in state legislation.

This is why we call them speculative vacancies.

They’re being held in lieu of speculative gains.

The outcome, however, doesn’t change.

When we get to the end of the cycle, and owners need to bail for financial reasons, the MSM story will change from an undersupply to the horrors of oversupply.

The rental crisis is unlikely to ease soon.

Authorities are under increasing pressure to implement reforms such as rent freezes — however, this does nothing to encourage underutilised sites onto the market.

There’s always the option of a vacancy tax.

Victoria implemented one just a few years ago.

However, it’s notoriously difficult to regulate and relies predominately on self-reporting.

Notably, it hasn’t substantially impacted vacancy trends, as Prosper Australia’s latest Speculative Vacancy report will prove.

To shift the market from a speculative one to one that works for need, not greed, requires sweeping tax reform.

Tinkering around the edges with vacancy taxes, first homebuyer grants, stamp duty to land tax changes, and so forth — cannot shift things substantially.

In another 10 years, journalists will still be writing about the same old woes of housing unaffordability. It’s a never-ending cycle.

The latest census data showed the number of people owning their homes outright has dropped from 41.6% in 1996 to 31% in 2021.

So, if you’re not renting from a private landlord, you’re likely renting from the bank.

Still, as renegade economist Michael Hudson quips, ‘rent that used to be paid to landlords is now paid to the banks as interest’.

This is why we have a boom/bust property cycle — and voters with skin in the game don’t want to do anything to stop the gravy train!

It reminds me of a comment by former Prime Minister Tony Abbott in 2015 (when the Sydney market rocketed some 15%-plus upwards in a year).

‘As someone who, along with the bank, owns a house in Sydney I do hope our housing prices are increasing…

‘I want housing to be affordable but nevertheless, I also want house prices to be modestly increasing.’

Indeed, there is nothing new under the Sun.

Best wishes,

|

Catherine Cashmore,

Editor, Land Cycle Investor

Comments