In today’s Money Morning…abandoning fossil fuels will be costly…capital cycles and underinvestment…fossil fuels and the all-or-nothing approach…and more…

As I walked with my coffee this morning, swathed in a sweater and coat, I thought about energy…

The energy needed to warm homes in winter and cool homes in summer.

The energy needed to get us all moving.

Energy sustains much of our modern life, and it is a testament to how well the system functions that we seldom need to think about energy at all.

But the recent spikes in prices, exacerbated by the war in Ukraine, brought the issue to the fore.

More specifically, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine made the issue of our dependence on fossil fuels more urgent.

As we shift ineluctably to renewables, what do we do about fossil fuels — and at what cost?

Abandoning fossil fuels will be costly

There is no such thing as a free lunch.

The energy transition is no different.

Our renewables future has great benefits — and costs.

But we may have neglected the cost ledger in our pursuit of cleaner energy.

In June 2020, the Brookings Institute summarised the optimism felt about the pandemic’s potential to accelerate change:

‘Some pundits are now asking if this crisis could be the push the world needs to move away from oil. One asked: “Could the coronavirus crisis be the beginning of the end for the oil industry?” Another: “Will the coronavirus kill the oil industry and help save the climate?” Meanwhile, 2020 annual greenhouse gas emissions are forecast to decline between 4–7% as a result of the virus’ effects, and some of the world’s smoggiest cities are currently enjoying clear skies.’

And in November 2021, The Guardian ran a portentous headline: ‘Half world’s fossil fuel assets could become worthless by 2036 in net zero transition’.

The article referenced a paper in Nature Energy, which argued (emphasis added):

‘In a worst-case scenario, people will keep investing in fossil fuels until suddenly the demand they expected does not materialise and they realise that what they own is worthless. Then we could see a financial crisis on the scale of 2008.’

Yet the worst-case scenario now seems quite the contrary.

People are not investing in fossil fuels enough and, suddenly, the supply of energy we expect is not materialising.

Yesterday, the BBC reported that a coal shortage in India coincided with a heatwave to create big power outages:

‘Two in three households said they were facing power outages, according to more than 21,000 people in 322 districts surveyed by LocalCircles, a polling agency. One in three households reported outages of two hours or more each day.

‘The main reason why electricity is in such short supply is a shortage of coal.’

The US is also feeling the pain.

Last week, the Wall Street Journal relayed a warning from US electric grid operators that power-generating capacity is lagging demand.

Current capacity is struggling and could lead to ‘rolling blackouts during heat waves or other peak periods as soon as this year.’

This isn’t a temporary problem either.

As the Financial Times reported overnight, some think the world’s energy woes will be a fixture for years:

‘“We don’t see wholesale prices returning to pre-crisis levels until the 2030s,” adds Tom Edwards at Cornwall Insight. “The world has changed and replumbing our energy system is not going to be cheap.”’

How did we get here?

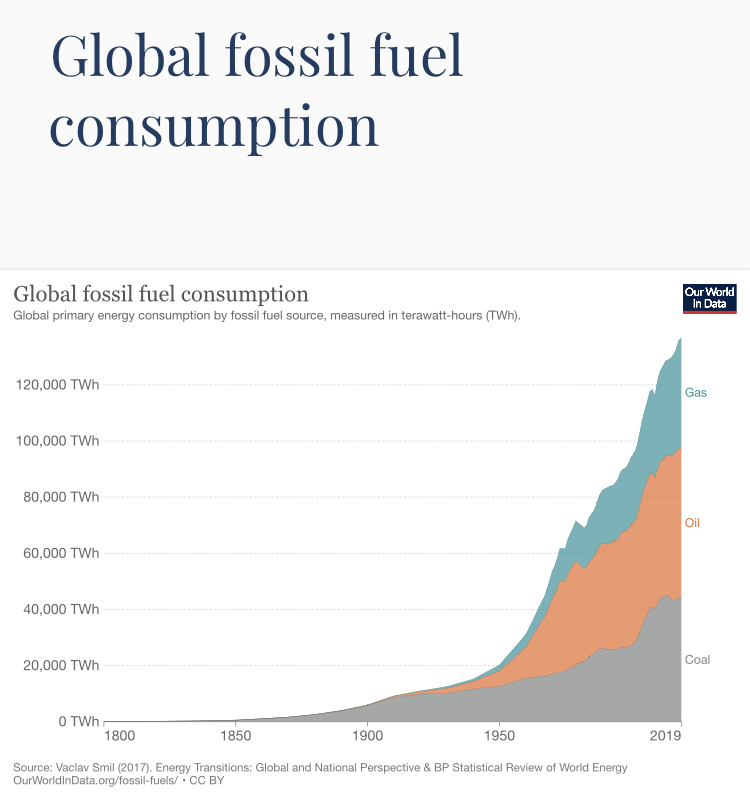

|

|

| Source: Our World in Data |

Capital cycles and underinvestment

In the same story warning about electricity shortages in the US, the Wall Street Journal pointed to the problem (emphasis added):

‘The risk of electricity shortages is rising throughout the US as traditional power plants are being retired more quickly than they can be replaced by renewable energy and battery storage. Power grids are feeling the strain as the US makes a historic transition from conventional power plants fueled by coal and natural gas to cleaner forms of energy…’

Economist Nouriel Roubini expanded on the logic earlier this year (emphasis added):

‘The politics of bashing fossil fuels and demanding aggressive decarbonization has led to underinvestment in carbon-based capacity before renewable energy sources have reached a scale sufficient to compensate for a reduced supply of hydrocarbons.

‘Under these conditions, sharp energy-price spikes are inevitable.’

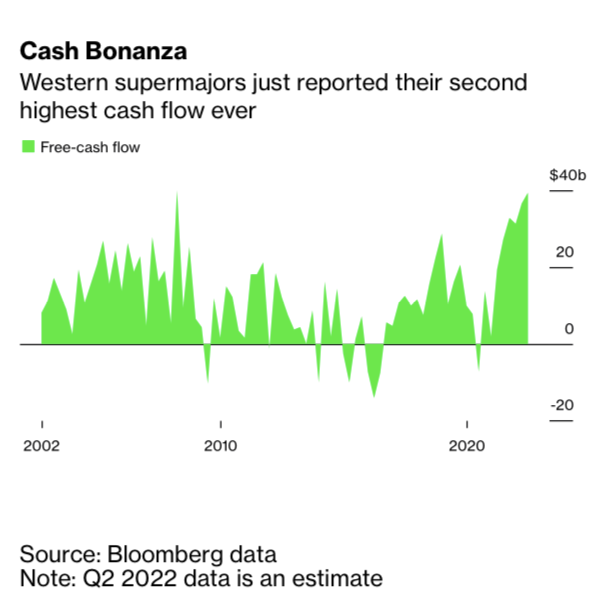

And while the article from Nature Energy forecasted half of the world’s fossil fuels to be worthless by 2036, the assets in 2022 are anything but.

Bloomberg reported this week that the West’s five biggest oil companies together posted US$36.6 billion in free cash flow in the first quarter.

That’s about US$400 million a day, the second-highest quarterly free cash flow on record:

|

|

| Source: Bloomberg |

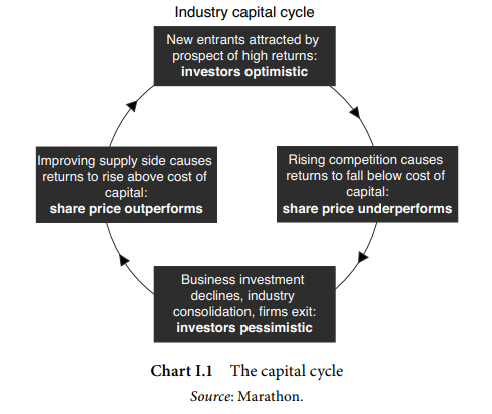

Usually, such large profits attract competition and ramp up of production.

Large returns on capital catch the eye of competitors, who try their luck in grabbing some of the pie.

But the attraction of more competition usually tends to drive returns on capital lower as business rivalry drives down prices.

This is neatly discussed in a great book by Edward Chancellor called Capital Returns.

In the book, Chancellor describes a ‘capital cycle’, which postulates:

‘Capital is attracted into high-return businesses and leaves when returns fall below the cost of capital. This process is not static, but cyclical — there is constant flux.’

Chancellor conceptualised the capital cycle in the diagram below:

|

|

| Source: Edward Chancellor |

But the capital cycle is unlikely to function properly in the context of fossil fuels.

Policies and incentives to divest from fossil fuels discourage competition, stalling the cycle and leaving incumbents with wads of spare cash.

After all, what company will invest in fossil fuels in today’s climate, even as profits rise?

What company wants to take on the risk of building a new plant — which takes years — when some are predicting that fossil fuel assets will be worthless by the next decade?

As a representative voice told Bloomberg earlier this month:

‘“In prior cycles of high oil prices, the majors would be investing heavily in long-cycle deepwater projects that wouldn’t see production for many years,” said Noah Barrett, lead energy analyst at Janus Henderson, which manages $361 billion. “Those type of projects are just off the table right now.”’

The last time crude oil was consistently more than US$100 a barrel was in 2013.

Yet that year saw Big Oil’s capital expenditure rise to US$158.7 billion, almost double what the companies are currently spending.

Some companies are even actively winding down some longer-dated projects.

In February, Origin Energy announced an ‘accelerated coal-fire exit’, shutting Australia’s largest coal-fired power plant a whole seven years early.

Origin CEO Frank Calabria admitted:

‘The cost of renewable energy and battery storage is increasingly competitive, and the penetration of renewables is growing and changing the shape of wholesale electricity prices, which means our cost of energy is expected to be more economical through a combination of renewables, storage and Origin’s fleet of peaking power stations.’

Fossil fuels and the all-or-nothing approach

And here is the conundrum.

Long term, renewables are the future.

Even the likes of Origin see this.

But fossil fuels may be necessary to facilitate a smooth journey to that future, especially given Europe’s likely accelerated divestment from Russian energy.

Consider the recent March quarterly from Whitehaven Coal (emphasis added):

‘While uncertainty remains whether the response to Russia’s actions in Ukraine will see a temporary or sustained shift in the high CV coal market, the potential is growing for structural change to occur. Replacement sources for Russian high CV coal supply are not readily identifiable with increasing potential for coal prices to find new highs for longer.’

As the Wall Street Journal aptly pointed out in April:

‘Another policy challenge is the need to encourage companies to make significant investments in fossil-fuel projects now, while also declaring that the nation’s goal is to make those projects obsolete down the road.

‘It’s hard to convince a company to make a multibillion-dollar investment in a pipeline that takes 30 years to pay for itself when the U.S. has embarked on a push to make the gas it carries unnecessary in 10 years.

‘Resistance to creating such “stranded assets” is a problem that will require some creative policy-making.’

The transition to cleaner energy is permanent.

No question about it.

But given the clear view of what’s coming, what do we do in the interim?

The fossil fuel phase out must involve more coordination: fossil fuels complementing the switch to renewables.

In 2016, three economists released a paper for the National Bureau of Economic Research.

In it, the authors concluded that as the push for clean energy continues, ‘it will be important to recognize the need for — and the costs of — complementary fast-reacting fossil backup technologies.’

Regards,

Kiryll Prakapenka,

For Money Morning

PS: The global transition to clean energy and the related phasing out of fossil fuels is a big axis shift. These events don’t come around often, but when they do, they shift the world on its axis. This offers opportunities for those who can anticipate these shifts before everyone else.

Few are better at anticipating such shifts than Jim Rickards. Luckily, he recently constructed a portfolio to leverage the latest axis shift. Go here to find out more about Rickards’ portfolio and reserve your spot.