The past month’s volatility has ruffled tech investors.

You’ve likely seen a fever pitch of articles questioning the sustainability of the Magnificent 7.

This is understandable, considering the run-up of these major stocks.

But judging whether that criticism is valid won’t help you decide whether to buy or sell.

As this past month has shown, markets can change in the blink of an eye.

You shouldn’t solely focus on the ticker tape or broader macro landscape to determine when to buy or sell.

Successful investment means being vigilant of market psychology — but also finding an edge.

‘The intelligent investor is a realist who sells to optimists and buys from pessimists.’

― Benjamin Graham, The Intelligent Investor

Here, I want to show you signals that will help you time your tech trades and move ahead of the market.

So, what is a better signal?

Hardware cycles

In the world of AI, the algorithms may grab the headlines, but it’s the hardware that turns those algorithms into real-world innovations.

Understanding this interplay and its timings will help you find good investment entries and exits.

Like most sectors, opportunities and business growth tend to cycle. You can think of it like the better-known real estate cycle.

This is typified by the periodic fluctuation in demand, production, and sale of a particular good — in this case, computer hardware.

These hardware cycles last between 2–4 years and are split between:

- Expansion: Increasing demand for new hardware, heavy investment, stocks rise

- Peak: Maximum output and sales, stock market saturation, profits compress due to competition

- Contraction: Low demand, heavy price competition, investment searches for new companies, tech/hardware

While these cycles generally follow the wider macro environment — like real estate — their timing is also its own beast.

Just take the 2008 financial crisis.

It took five years for the S&P 500 to recover to its pre-crisis peak and three years for US GDP to return to pre-GFC levels.

At the same time, cell phone investments and hardware bucked that trend. Remember, the iPhone was released in June 2007.

If you followed the macro sentiments, you missed out on that trade — as many fund managers did.

Inventions like the iPhone and AI are hard to predict and even more difficult to judge their impact. It’s unlikely you’ll find the investment idea of the decade.

Instead — like many people do with real estate — think about positioning yourself to invest heavily when the next cycle turns.

How can we determine those cycles? And where are we now?

Before we get there, let’s revisit 2010’s for a bit of history to learn how we got here.

Our current cycle: AI and GPUs

In the early 2010s, identifying images was the major problem for AI to solve.

A competition known as ImageNet was the crucible for testing AI solutions to this problem. ImageNet used a dataset of more than 15 million high-resolution images hand-labelled by humans.

AI researchers would spend the year tinkering and creating AI that would try to identify and correctly label images.

This was done by giving five labels to each image and choosing its best guess of the lot.

Here is an example of what those results might look like:

A winning solution to this problem was a quick way to cement yourself in the early world of AI.

Past competition winners went on to senior roles at Google, Baidu, Huawei, and DeepMind.

The holy grail of this competition was to achieve a top-5 error rate of less than 25% in the challenge.

That would mean having the correct label somewhere in those top five guesses at least three out of four times.

And the competition was certainly heading in that direction.

In 2011, the top-5 error rate was down to 25.8%, and many in the field were ready to celebrate in the coming year when the goal was finally surpassed.

And then something came in and flipped the table…

The next year the goal was not only passed, but absolutely smashed by a system known as AlexNet.

While that improvement might not seem like much to us, the outperformance wasn’t lost on the AI crowd.

For a competition that was used to 1–2% improvements each year, the introduction of AlexNet sent a shockwave through the field of AI.

By using a new architecture that allowed it to use two gaming GPUs, AlexNet redefined how AI functioned. Its ideas kicked off a new wave of AI research into Deep learning.

The AlexNet paper has now been cited around 160,000 times. It was essential in showing how AI can use GPUs rather than traditional CPUs during AI training.

The two main authors, Alex Krizhevsky and Ilya Sutskever saw their startup acquired by Google within months.

Illya then became the principal architect of the ChatGPT systems at OpenAI, which began our most recent wave of AI hype and research.

While it’s not a straight line from AlexNet to here, it’s a major signpost on the road to our current world where GPUs have become the epicentre of the Mag 7.

This story is worth remembering if you believe GPUs will remain at the centre beyond this cycle.

While everyone is focused on using these chips to drive the next generation of AI, things will likely change again when the next cycle begins.

Even OpenAI’s Sam Altman has said new architectures and AI investments are needed on the road to Artificial General Intelligence (AGI).

He has also personally invested in Rain, a startup in the neuromorphic chip space similar to our own home-grown Brainchip Holdings [ASX:BRN].

It’s hard to say if this new computing is the future.

Many things are likely to change in both AI and hardware between now and then.

But think about positioning yourself so you have capital to allocate when the next cycle churns.

So, what are some of the signs to look for when determining hardware cycles?

Supply chains and spending

Respected investment strategist Russell Napier once said:

‘Analysts spend 90% of their time thinking about and forecasting demand and 10% of their time thinking about supply’.

This insight is particularly relevant to hardware cycles and the semiconductor industry.

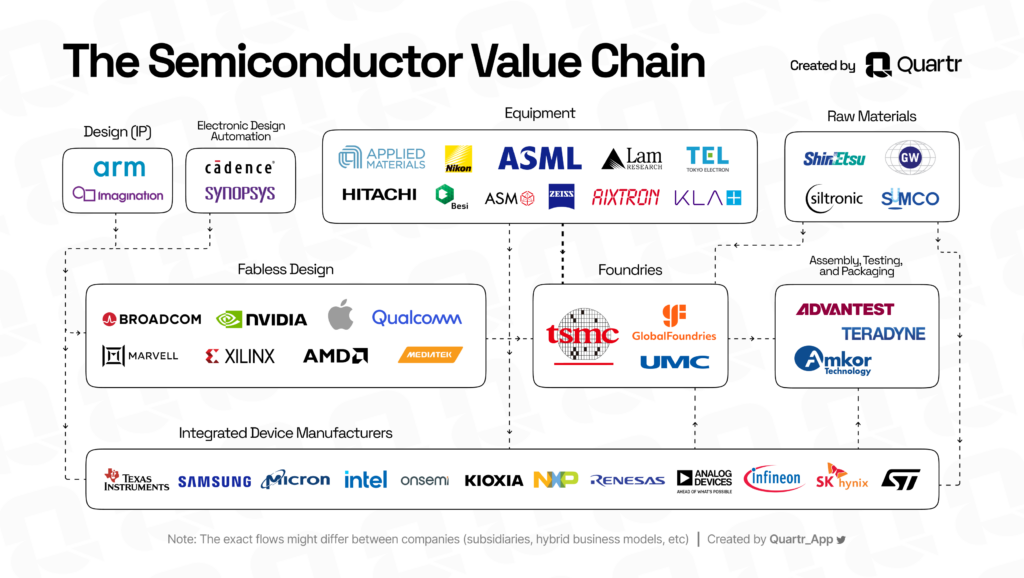

This supply chain forms the backbone of AI, and understanding its dynamics can give you a strong edge in investing.

Here’s a broad picture of the major players in the sector:

This supply chain can be volatile and subject to significant cycles of shortage and excess.

That’s because one cog in the supply chain will inevitably overproduce older tech while everyone else screams for newer hardware further down the chain.

Finding these over and underproduction problems can give you insights before most investors.

For example, COVID triggered a global chip shortage that reverberated through many industries, including AI.

Consequently, overbuying became a clear trend in the semiconductor industry. Manufacturers double-ordered many components to avoid facing shortages again.

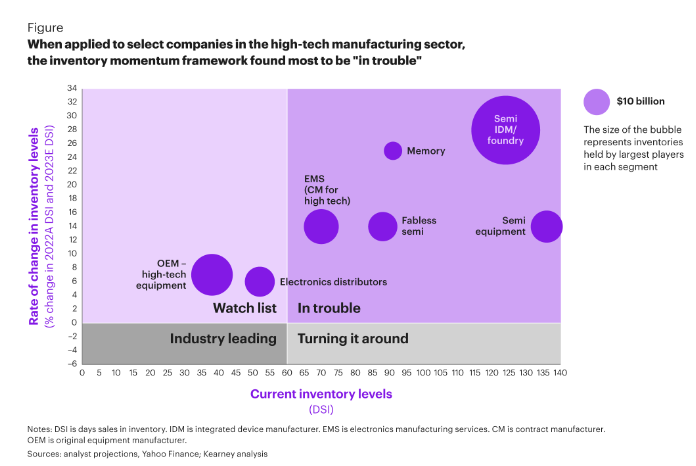

Around the first quarter of 2024, companies held inventories around twice that of 2019.

According to a 2023 Kearny study, excess inventory has become a $250+ billion problem in the electronic component industry.

This oversupply could become obsolete as technology and hardware advance, forcing huge discounts.

Something that could be seen on the balance sheets and earnings reports recently.

But components are just one small part.

What should you look for in hardware supply chains?

First, find frontline companies that help manage these inventories. A useful one I’ve found is Fusion, whose monthly reports can give valuable early signals.

But what are the major things to look for, and what do they mean?

Semiconductor Equipment Orders: Companies like ASML, Applied Materials, and Lam Research provide the tools to manufacture chips. Their order books can be leading indicators of future chip supply.

A good example is Applied Materials’ earnings last week. It showed a mixed sales report from China and a wide variance in its fourth-quarter forecast.

What did it point to as a potential winner? High-bandwidth memory.

‘We have seen demand for high-bandwidth memory accelerating in 2024 and expect to generate more than $600 million of HBM packaging revenue this year, which is approximately six times 2023. Overall, including HBM, we expect revenue from our advanced packaging product portfolio to grow to approximately $1.7 billion in 2024.’

Inventory Levels: Pay attention to inventory levels reported by major chip manufacturers and their customers.

Excessive inventory build-up can signal an impending slowdown, while lower inventories might indicate an upcoming surge in demand.

NXP Semiconductors, a major player in the semiconductor industry, recently reported:

‘In the automotive sector, revenue decreased due to ongoing inventory digestion challenges with direct Tier 1 customers. Although this trend will likely continue into the second half of the year, sequential growth is anticipated as inventory adjustments progress and new platforms ramp up.’

While AMD’s recent reporting showed a 59% decrease in its gaming unit’s revenues, noting:

‘The decrease in revenue was primarily due to semi-custom inventory digestion and the lower-end market demand.’

Capital Expenditure Plans: Major tech companies and chip manufacturers often announce their CapEx plans for the coming year. These can give insights into expected demand and technological shifts they are seeing.

All the major tech players have said they intend to continue investing heavily in AI hardware. As the race for AI supremacy continues, keep a close eye on their CAPEX spending in the next quarters to see if anything softens.

Foundry Utilisation Rates: Companies like TSMC and Samsung, which manufacture chips for many tech giants, report factory utilisation rates. High utilisation rates can indicate strong demand but also potential supply constraints.

TSMC reported utilisation rates of 95% in June, while the South Korean semi’s average is around 75% — above the normal 60–70% rates.

Meanwhile, memory manufacturers have reached 90–100% rates and have noted completely sold-out stock for 2024 and most of 2025.

Lead Times: Extended lead times for chip orders can indicate strong demand or supply chain bottlenecks. Meanwhile, shortening lead times might signal an easing demand or an increase in supply.

This reporting season has seen probably the last mentions of ‘normalisation’ across supply chains as we leave the pandemic’s problems behind.

Could that signal a peak in the cycle?

No clear answers, only signals

These are the broad strokes investors can look for when making decisions — but it’s not gospel.

It’s important to understand that different hardware market segments recover at varying rates.

While some areas may see quick turnarounds, others could face prolonged periods of oversupply or undersupply.

The memory chip market is perhaps the best example. After a period of oversupply and price drops, renewed demand from AI has boosted the market.

Companies like Samsung and SK Hynix now resuming equipment investment in response to this shift.

This could prove a good time to look into other players in the space too.

Given the rapid pace of AI advancement, focusing on companies investing heavily in cutting-edge manufacturing processes could also be a winning strategy.

Those at the forefront of advanced nodes will likely be better positioned for AI-driven growth. Cutting-edge chips will usually be favoured to meet the demands of more powerful and efficient AI hardware.

But that doesn’t mean you should only buy these sectors’ stocks.

Investors should spread their capital across various components and technologies to create a balanced portfolio that can weather the ups and downs.

While quarterly results can give insight, successful investments often require a longer-term perspective.

The cyclical nature of the semiconductor industry means that short-term fluctuations don’t always reflect long-term value.

Investors should be prepared to hold positions through market cycles, focusing on the overall trajectory of AI adoption or their chosen hardware.

Remember, the next breakthrough product doesn’t appear in immaculate form. Somewhere, a factory is sourcing and building its components.

Keep an ear to the ground, and you’ll move ahead of the market.

Regards,

Charlie Ormond

Tech Analyst for Alpha Tech Trader

Comments