More good news on rates…Reuters, 2 September 2023:

|

|

| Source: Reuters |

To quote from the article:

‘“This [Labor Department] report is likely to put the Fed on hold in September, and if we get more positive inflation news in September and October, the Fed is likely done, and we’ve seen the end of the rate hikes,” said Peter Cardillo, chief market economist at Spartan Capital Securities.’

The Labor Department report Mr Cardillo referred to, ‘showed the unemployment rate jumped to 3.8% last month, from 3.5% previously’…I’d say it’s more of a little step up than a ‘jump’.

Mr Cardillo (and many, many others) are expressing collective sighs of relief over the ‘probable’ end to interest rate hikes.

The narrative peddled by those with short memories and long market positions goes something like this, ‘with interest rates (all but) tapped out, share markets can get on with the business of going higher and higher and higher’.

Simple really. But that’s the problem…nothing with markets is ever simple.

Another popular narrative from The Wall Street Journal:

|

|

| Source: The Wall Street Journal |

According to the article (emphasis added):

‘In an era of unprecedented, technology-fueled growth, a soft landing of the economy has emerged as the Holy Grail of US policymakers. But the continued growth of the economy is feeding a running debate among economists about whether the economy needs to be landed at all.’

Here’s The Wall Street Journal headline again, only this time I’ve included when the article was published…11 August 2000:

|

|

| Source: The Wall Street Journal |

As reported by The Balance, the 2001 landing, when compared to what would come in 2008/09, was softish, at least for those who kept their jobs (emphasis added):

‘The 2001 recession was an eight-month economic downturn that began in March and lasted through November. While the economy recovered in the fourth quarter of that year, the impact lingered and the national unemployment continued to climb, reaching 6% in June 2003.’

Unemployment is ‘bound’ to rise

If we look at the picture of unemployment, we’ll see it too has a repeatable pattern.

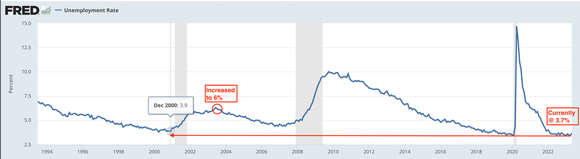

In December 2000 (a few months after The Wall Street Journal article) US unemployment hit a low of 3.9% (eerily close to today’s 3.8%).

|

|

| Source: FRED |

The Dot-com Bubble was a job creator.

More start-ups needed more staff. Suppliers (hardware and software) to the fledgling tech industry, employed more staff. And, in general, people feeling wealthier (on paper) tend to spend more.

Technology-fuelled growth had been a boon for the jobs market.

The operative word in the above sentence is…had.

When the technology-fuelled growth ran out of fuel, jobs were shed…unemployment bounded, not jumped, to 6%.

And, what happened in early 2000 was repeated during the US Housing Bubble and bust.

If we go back to the US unemployment chart, you’ll see that as the US Housing Bubble was inflating, the unemployment rate fell. Again, the pattern repeats. An expanding (some would say, overheating) economy created more employment opportunities.

Then came the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) and it was a case of ‘whooshka’ on the employment front…job losses went vertical.

But none of this is new news.

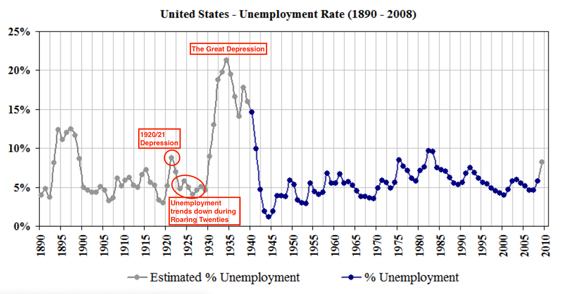

After unemployment spiked in the 1920/21 Depression (yes, there was a Depression before The Great Depression), the recovery period — famously referred to as ‘The Roaring Twenties’— saw unemployment numbers trend down. A booming economy was great for the labour market.

Along came the October 1929 crash, followed by The Great Depression…unemployment didn’t jump…it soared.

|

|

| Source: Wikipedia |

The story of unemployment numbers being compressed before a recoil is one that’s been told many times over the past century.

Therefore, based on history, when headlines like the one from Reuters imply ‘all appears okay’, it should be cause for heightened concern, not laid-back complacency.

A pause for thought

Besides The Wall Street Journal pondering whether a landing was even going to happen in 2000/01, are there any other similarities between then and now?

And what could have possibly caused the recessions and job losses?

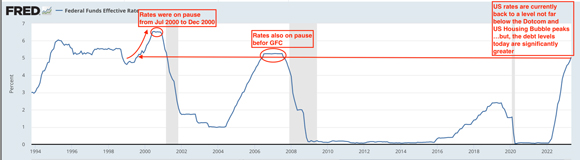

Prior to the busting of both previous bubbles, the Fed had been raising rates and then…they paused.

The collective thinking was (as it is today), ‘phew, the worst is over’.

Sorry — if history is any guide, the worst is yet to come.

The ‘pause period’ is when those who held on and held on during the successive rate increases can no longer hold on. The stresses of continually trying ‘to rob Peter, to pay Paul’ become too great and the white flag goes up. That’s when defaults beget defaults.

Look where rates are today, compared with the peaks of the two previous bubbles…

|

|

| Source: FRED |

What’s different between then and now?

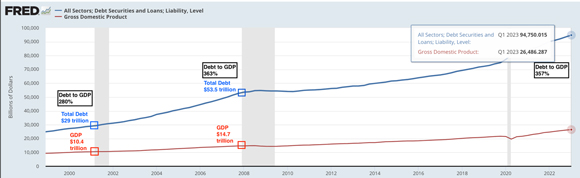

The debt load.

In dollar terms, the amount of US debt today is significantly greater and, on a debt-to-GDP basis, is on par with the level prior to the GFC…this can’t be good.

|

|

| Source: FRED |

How much of that US$94.75 trillion debt pile is at risk of default?

Zombie corporates. Commercial property borrowers. Stretched households (especially if job losses start mounting up). Municipal Bonds (local and state governments with falling tax revenues).

Could the number of ‘at risk loans’ be (say) 5% of the debt pile?

If so, that would be almost US$5 trillion (which equates to 20% of US GDP).

When this number is compared to the US$300 billion in subprime lending that triggered the GFC, you can see why the situation is a potential ‘powder keg’.

There are several similarities in the pre-bust phase of bubbles past and now to warrant a more conservative approach to your asset allocation.

However, the current bubble has another element to it that, in my opinion, takes the danger level to an extreme.

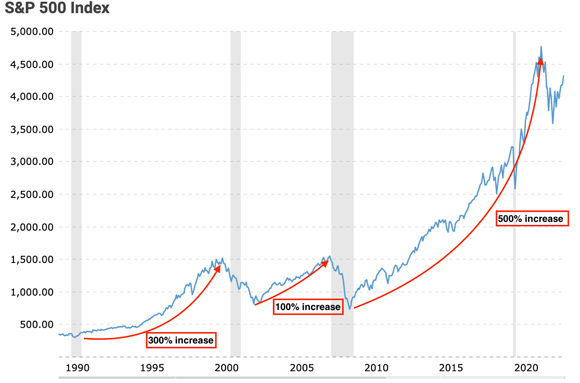

The degree of speculation within society is beyond anything we’ve seen in recent history…

|

|

| Source: Macro Trends |

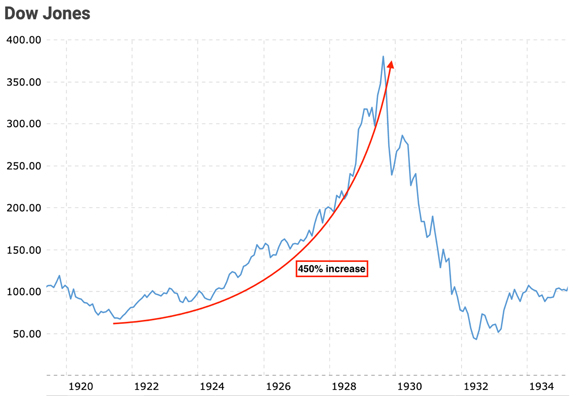

And, if we go back a bit further in market history…

|

|

| Source: Macro Trends |

Each one of these episodes, including the NASDAQ’s powerful surge from 1995–2000, all, I repeat all, ended with corrections/collapses ranging from almost 50–90%.

Is all the pre-bubble bursting history on complacency levels, unemployment numbers, interest rates and pauses, excessive debt levels and exponential market increases, to be dismissed as a mere coincidence? OR should it give us all pause for thought on what might be coming our way in the not-too-distant future?

Those with little understanding of market history should be careful of what they wish for…a pause in rates has in the past been bad, not good, news for market fortunes.

Until next week

Regards,

|

Vern Gowdie,

Editor, The Daily Reckoning Australia