Growth stocks are great…

Tech stocks have captured investors’ imaginations for the last few decades for many reasons.

Growth is one of the biggest.

Unlike cyclicals or companies operating in staid industries, tech stocks seem to have an endless sales runway.

New or improved technologies lead to more customers, more customers boost sales, and rising sales sustain growth.

I’ve wrote about the importance of growth a few weeks back.

No one denies the potential of growth stocks.

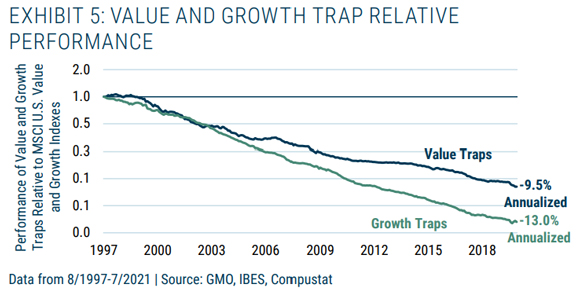

As global investment firm GMO noted in a quarterly a few years back, growth stocks have historically notched some of the best gains:

‘It is almost invariably the case that the greatest buy and hold returns will come from successful growth companies. One dollar invested in Amazon on July 1, 2001 would have turned into almost $267 twenty years later.’

The greatest ‘buy and hold’ returns may come from growth companies, but identifying these companies isn’t as easy as glibly stating that growth stocks are the road to riches.

As GMO later noted in the same quarterly (emphasis added):

‘But however obvious it may appear in retrospect that Amazon would become a colossus, picking winners is hard and the consequences of guessing wrong are generally severe. While it is not a fair analogy to equate buying Amazon stock 20 years ago to the purchase of a winning lottery ticket, what the two have in common is that an ex-post analysis of the results from those two outcomes is a lousy guide to the return to the general activity — purchasing highly priced growth stocks and purchasing lottery tickets.’

|

|

| Source: GMO |

A lottery winner should not conclude from their success that buying lottery tickets is a viable money-making enterprise.

Similarly, an investor who tipped a successful high-growth stock should not from this fact alone conclude growth stocks in general are foolproof.

…but growth at what price?

Growth is alluring.

But what price should you pay for it? Can you overpay for growth?

Certainly.

Growth that’s already priced in by the market is unlikely to generate superior returns. And growth that’s priced in that doesn’t eventuate leads to sharp disappointment.

By the way, the issue of what’s priced in drives the latest Fat Tail podcast with Greg and I.

Anyway, back to growth and the issue of price.

What is the growth premium? And does it have a ceiling? Does price even matter for a company with bountiful growth prospects?

In every bull market, you’ll find investors who’ll say price is almost irrelevant if a company’s future fundamentals are outstanding (like Amazon’s were in the early 2000s).

But as GMO noted, growth at any price does have costs:

‘Our quarrel in any event is not with growth stocks per se, but the idea that you can buy stocks without regard to the price you are paying because the future fundamentals will be so wonderful that the price is irrelevant. When growth stocks are trading at a relatively modest premium to the market, we generally forecast that they will outperform, and we did so more or less continually in the U.S. from the fall of 2004 until the middle of 2015. When the premium gets significantly wider than historical averages, we start to get nervous, and when we see the premium get to extremes, we start to wonder if speculative mania has set in.’

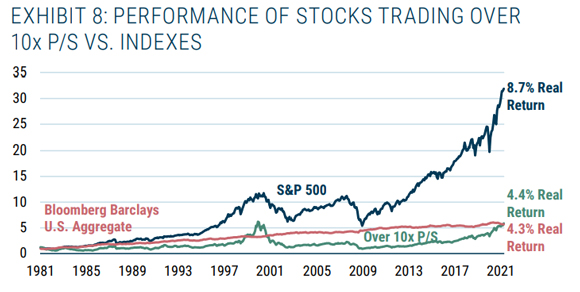

The investment company then shared one of the most illuminating charts I’ve stumbled across recently.

The chart depicts the long-term performance of stocks trading over 10 times their sales (that is, with a price-to-sales ratio of more than 10).

When jubilant investors pay up for growth, the P/S ratio of the relevant stocks rises. But what’s the average return of stocks trading at 10-times sales?

Not great, as you can see below:

|

|

| Source: GMO |

The 10-times sales stocks underperformed the market by more than 4% per year since 1980.

What’s the takeaway? As GMO put it (emphasis added):

‘While it is not impossible to prove worthy of such a high valuation, it takes extraordinary results to do so. And investing where it will take something extraordinary to earn a good return has generally been a bad idea despite the existence of a handful of exceptions to the rule.’

To illustrate, consider the extraordinary results a stock like Nvidia requires to prove worthy of its current valuation.

I’ve quickly tabulated the current trailing price-to-sales ratios for the eight mega-cap tech stocks driving the US market higher this year.

|

|

As you can see, Nvidia is the huge outlier, with a P/S well over 10 times.

Given its current market capitalisation of ~US$970 billion, Nvidia’s sales would need to reach US$97 billion just to warrant the still-heady P/S of 10.

Nvidia’s latest full-year sales figure was ~US$27 billion.

Consensus estimates have the chipmaker making ~US$63 billion in sales by FY26, so the US$97 billion marker is way out in the future.

Attainable? Maybe.

But as GMO quipped, ‘investing where it will take something extraordinary to earn a good return has generally been a bad idea’.

Bulls will argue Nvidia is the exception, given the exceptional nature of the market it serves — artificial intelligence.

Time will tell.

Interestingly, the rest of the mega-cap tech stocks are trading at reasonable P/S ratios but still elevated.

The historic S&P 500 P/S ratio is around 1.7.

People are still happy to pay up for these giants, banking on continued growth derived from market-leading positions.

Ed Yardeni of Yardeni Research pointed to some dizzying metrics last Friday:

‘The forward P/E of the MegaCap-8 was 29.6 on Friday. Excluding them, the forward P/E of the S&P 492 was 15.6. Most astonishing is that the MegaCap-8’s market cap has melted up by 58.1 per cent from this year’s low of $US6.8 trillion on January 5 to $US10.7 trillion through Friday’s close.’

I’ll leave you with a study from Verdad Capital, which looked at US stocks from 1997 to 2022.

It found ‘little to no evidence of persistence in earnings growth, beyond chance, over the long term’, echoing an earlier 2001 paper that concluded:

‘While some firms have grown at high rates historically, they are relatively rare instances. There is no persistence in long-term earnings growth beyond chance.’

Growth does not persist forever.

The rare exceptions are lucrative and tend to prove the iron rule of the mean.

Regards,

|

Kiryll Prakapenka,

Editor, Money Morning