The most common question I get emailed by subscribers is ‘Will the cycle peak early?’.

It’s almost impossible for some to buy into the notion that land prices can climb higher, considering the rapid hike in lending rates in recent times reducing purchaser’s budgets and hitting consumer confidence.

Property forecasts for 2023 from most major data agencies remain negative (with 11%-plus declines expected).

The only one currently bucking the trend is SQM Research. Founder Louis Christopher expects a modest recovery ahead. You can listen to his reasoning in a recent chat I had with him here.

Still, our analysis at Land Cycle Investor isn’t just based on what we read in the daily news.

If it were, the forecasts from this service would be no different to those of the major banks.

They’d be like throwing a dart into a dartboard, shifting direction every quarter or so depending on conditions at the time.

Everything we do here is based not only on the analysis of current economic drivers, but it’s also backed by a historical understanding of the property cycle.

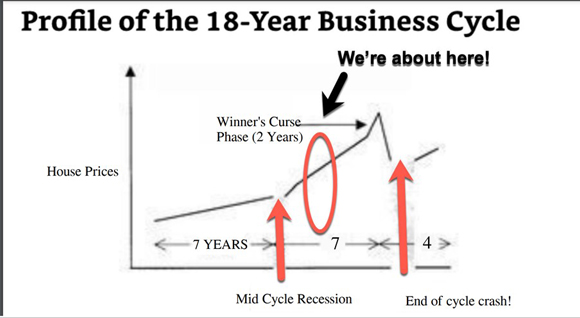

As Cycles, Trends & Forecasts subscribers will know, the real estate cycle in Australia correlates with the 18-year cycle that is evident in the US and Europe.

Let’s briefly break this down so you’re aware of how it looks.

In his 1983 book, The Power in the Land, UK land economist Fred Harrison identified a consistent, 18-year movement in land values over more than 400 years of English history.

This allowed him to forecast the 1990s land price-led recession some eight years in advance.

The late Fred Foldvary, economist and lecturer in economics at San Jose State University, California, identified an identical pattern in the US, tracing it back to the early 1800s.

The basic breakdown of the cycle is 14 years of generally rising land values, plus four years of falling property prices.

However, bear in mind, the rise in property prices can go for longer (up to 16 years, historically) and then fall shorter. They can also peak and stagnate early, however, this is more evident on a local basis (for example, Sydney’s median values peaked in 2004 and stagnated until the GFC hit).

It largely depends on local policy and the level of speculation in the lead up.

What is consistent, however, is that there will be two recessionary points in the cycle.

First, the mid-cycle recession midway through.

This does not lead to a crash in real estate values.

However, it will affect the stock market, and can push the general economy into either a major or minor recession. This is what we’ve just experienced with the COVID panic through 2020–21.

In contrast, the end of cycle recession will crash the real estate market if speculation has been strong in the run up. (Therefore, the cycle — when looking at real estate data — tends to be most evident in major city markets, rather than remote areas that lack speculation and remain consistent and low in price.)

The only exception is if there’s strong government intervention to prevent the downturn in prices, as Australia saw in 2008 during the global financial crisis.

I’m talking about substantial home buyer grants, stamp duty cuts, and so on.

In Australia, we’re now in the fourth ‘Grand Cycle’ since the Second World War.

A consistent boom/bust real estate cycle.

The dates for the first three ran as follows:

- The first cycle 1955–74

- The second cycle 1974–92

- The third Grand Cycle 1992–2010

Our current cycle runs from 2010 to a bottom around 2028, should history repeat itself.

We’re currently in the second half that should take us to a forecast peak in property values in 2025/26.

Here’s a stylised view of the cycle so you can get the gist:

|

|

| Source: Catherine Cashmore |

In short, I’m not expecting an early peak to the cycle. I think there are enough drivers ahead to turn the market back into positive territory through 2023.

Which brings me back to the question at hand…what could possibly produce a rise in real estate values against the negative news in the mainstream media?

There are few factors to note. We’ll go into in more detail on each in future editions…

- Population growth into markets that are limited in supply.

- Rises in rental prices placing pressure on existing supply.

- Technology — assisting an increasing number of fintech lenders into the property market lending space — and blockchain technology aiding fractionalised lending models.

- Strong indicators showing inflation is slowing and the prospect of the RBA pausing as we transit through 2023.

- State home buyer incentives, such as the switch from stamp duty to land taxation in NSW assisting to boost the lower end of the market. This is something that will likely produce a wave across the whole market as those selling properties at the lower end will have more to upgrade.

- Rising commodity prices assisting markets exposed to this driver, Perth, for example.

For now, let’s focus on population growth.

Net arrivals into Australia accelerated to 200,000-plus in October.

Arrivals have been outpacing departures since July.

2023 will likely be a record year for population growth in Australia, and that’s going to place a significant challenge on property markets in the cities capturing the bulk of the inflow (Sydney and Melbourne, in particular).

Notably, migrants are renters before they are buyers. And annual growth in rental values continues to accelerate.

|

|

| Source: CoreLogic |

Since COVID, the building industry has been subject to natural weather disasters, substantial increases in the price of building materials, major supply chain disruptions, and labour shortages.

There’s no big influx of supply to ease conditions in the shorter term.

Therefore, it’s expected that rents will continue to rise through at least the first half of 2023 as a result. And as mentioned previously, this ultimately places upward pressure on land values in areas of short supply.

For investors, population growth flowing into areas that are short on supply is the beginning of the gentrification flow chart.

In Australian history, price rises have always started with this initial ingredient.

In fact, I’ve made a flow chart to show how it works:

|

|

| Source: Catherine Cashmore |

Just look back at what happened during COVID as an example.

Massive interstate migration flooded into regional areas, producing an unprecedented wave of inflation in markets not equipped to manage the influx.

Regional Victorian house prices, for example, grew at the fastest rate in 20 years through 2021.

That kind of inflationary boom cannot be sustained without a pullback or a continuation of the factors that produced it.

And in this case, population is now making a return to the cities, and the stimulus provided over the pandemic is no longer relevant.

I expect the government will step up at some point to incentivise the building industry so it can meet its ‘one million well-located homes in five years’ promise.

And considering the number of first home buyers has halved since the peak in 2021, how long before we see a few more incentives to encourage them back into the market?

As I said, I’ll touch on the other drivers that could potentially push prices higher in future updates.

For now, however, I think it’s safe to say we’re not there yet…

Best wishes,

|

Catherine Cashmore,

Editor, Land Cycle Investor

Comments