Bowser shock is the new epidemic striking Australians. And cycling to work has never looked more appealing.

Current petrol prices are so high you can match them to legendary Test innings.

Ah, yesterday’s price was $2.11 a litre, that’s what Steve Smith hit at Old Trafford in 2019 in the Ashes.

Today’s price is $2.20, that’s what Ricky Ponting hit at the Adelaide Oval in 2012 against India.

New Zealand’s petrol prices may soon run out of cricketing comparisons, set to hit NZ$3.50 a litre by Christmas.

|

|

| Source: MotorMouth, AIP, CommSec |

What’s going on? Why are petrol prices so high?

Part of the answer lies with Australia’s refining capacity.

The drivers of Australia’s petrol prices

What determines what we pay at the petrol station? What are the key components of retail petrol prices?

The key inputs that make up what we pay at a local station are quite simple:

- International cost of refined petrol

- Taxes

- Retail margins (service stations have to make money, too)

- Wholesale margins (shipping costs and import costs)

The ACCC publishes a quarterly report on the Aussie petroleum market.

The latest report, for the June quarter, showed that 50% of the retail petrol price is eaten up by the international cost of refined petrol.

This and taxes accounted for 83% of average petrol prices. As ACCC noted, these components are ‘largely outside the control of local petrol retailers’.

We are at the whim of global markets.

|

|

| Source: ACCC |

And this cost to import refined petrol is the main reason why prices are so high right now. And why they are likely to remain high.

Australia’s reliance on refined petrol imports — why Mogas 95 is king

Australia’s local refining capacity can’t meet all our fuel needs. So we import most of our refined petrol from international markets.

The most important international benchmark for Australia is the price of Singapore Mogas 95.

Mogas 95 is used to price petrol in Australia due to Singapore’s proximity and role as one of the world’s most import refining centres.

Two immediate corollaries stand out.

Since we import Mogas 95, we are by proxy exposed to movements in international crude oil prices…and the exchange rate.

As the ACCC noted in its report:

‘Movements in retail petrol prices in Australia are largely determined by movements in international refined petrol prices and the AUD–USD exchange rate.

‘The AUD–USD exchange rate has a significant influence on Australia’s retail petrol prices because international refined petrol is bought and sold in US dollars in global markets.’

A weak Aussie dollar makes importing Mogas 95 more expensive and, by extension, the petrol we buy at local stations.

And the Aussie dollar has been historically weak in recent years against the USD.

With worries about China’s economic health, the Aussie dollar is likely to remain weak for a while yet.

That’s not good for local petrol prices.

Australia’s waning local refining capacity

But why do we have to import so much refined petrol?

Why can’t we do it ourselves?

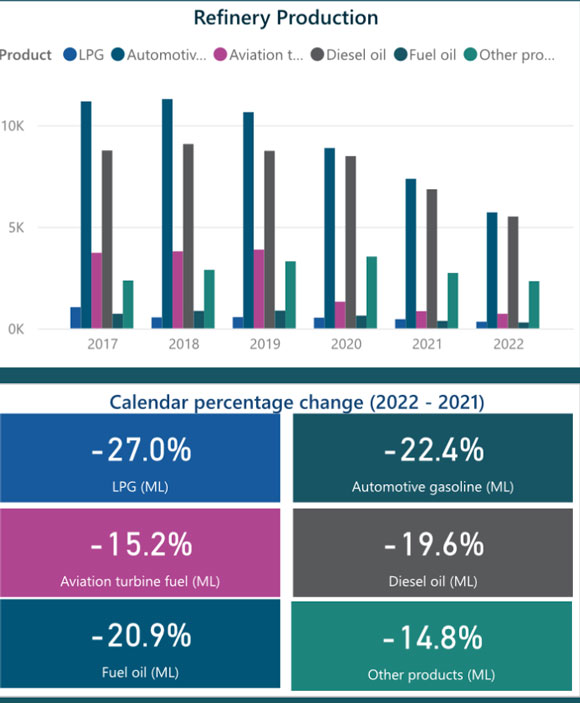

Local refined production has been falling steadily for years.

|

|

| Source: energy.gov.au |

And the problems with local production have been known for years, too.

In 2015, the Business Council of Australia made a submission to the ACCC East Coast Gas Inquiry.

The submission was 85 pages and broached a swathe of energy topics, but the section on Australia’s refinery capacity concerns us here.

Already in 2015, the Business Council was saying Australia’s refining industry faced ‘considerable challenges’:

‘However, Australia’s refining industry faces considerable challenges, including intense global competition from larger, more efficient mega-refineries, and surplus capacity in foreign regional markets.

‘These factors have challenged the viability of Australia’s refineries, which are now seeking to manage pressures through efficiency gains and by reducing costs.’

The story of Australia’s local refining industry is one of globalisation.

In open markets, local refiners have struggled to compete with cheaper, more efficient global rivals.

Instead of persevering against all economic sense, the refiners listened to the adage of comparative advantage and folded operations.

As the Council’s submission explained:

‘Global rationalisation of the liquid fuels industry is occurring due to the significant growth and expansion of refining capacity in Asia, which now outstrips demand. Europe and the US are also rationalising their liquid fuels markets, with eight European refineries closing since 2009.

‘The mega-refineries in Asia have lower operating costs, are more fuel efficient, have more sophisticated processing facilities and can produce large quantities of high-quality products from cheaper oil and feedstocks.

‘Asia’s mega-refineries benefit from significant competitive advantages in terms of economies of scale, latest technology and costs. Output for each of Australia’s oil refineries (prior to recent closures) ranged from 75,000 to 138,000 barrels per day (bpd). Modern plants produce at least 200,000 bpd, and the world’s largest refinery, in India, produces over 1.2 million bpd — roughly 50 per cent more than Australia’s total production.’

Australia now only has two local refineries, operated by Ampol and Viva Energy, after ExxonMobil decided to convert the Altona refinery in Melbourne to an import terminal in 2021.

Why did ExxonMobil stop refining in Australia?

ExxonMobil is one of the world’s largest refiners, with 5 million barrels per day of distillation capacity.

It knows what it’s doing.

And Exxon decided it was in its best interest to converting the Altona refinery into an import terminal.

Exxon said the Altona refinery was ‘no longer considered economically viable’.

Exxon doesn’t think all refineries are uneconomical, just the ones in Australia.

Its global refineries, for instance, are doing just fine.

In FY22, Exxon said its global refinery throughput reached its highest annual level since 2012.

It even expanded the output of one of its key refineries by an additional 250,000 barrels per day.

Free markets and the energy transition

Australia’s reliance on imported refined petrol is largely a result of free markets at work.

If local refiners were somehow coerced to continue operations, Australians would be paying much more at the bowser to compensate local refiners’ high costs.

Instead, we get to import quality refined petrol from ultra efficient mega-suppliers in Asia.

The downside is exposure to crude oil and exchange rate moves, variables beyond fiscal and monetary control.

But some energy issues can be influenced by governments.

To detrimental effects.

That’s the conclusion of extensive research by our editorial director Greg Canavan. Greg has spent months digging into Australia’s Net Zero ambitions.

He thinks the plan to decarbonise Australia is overly ambitious and is doomed to fail.

But he thinks investors can benefit from what he calls the ‘biggest energy U-turn in history’.

You can check out his recently released research here.

Regards,

|

Kiryll Prakapenka,

Editor, Money Morning