With the US government shutdown nearing resolution — after Democrats appeared to cave — data nerds and quants can breathe a sigh of relief.

For the past month, the federal shutdown has halted almost all economic data.

Many on Wall Street, as well as Fed Chair J. Powell, have described this period as ‘flying blind’.

After the late October interest rate cut, Powell used that pretext to warn that it could be for the last time this year.

‘What do you do if you’re driving in fog? You slow down,’ J Powell noted.

That’s a bit of an overstatement; there are plenty of unofficial, private sources that have given us some indication of the health of the US economy.

But the key ones remain withheld. According to White House Press Secretary Karoline Leavitt, October’s jobs and consumer price index reports are ‘unlikely to be released’.

Are they unlikely because the data is bad — or because the bureaucracy needs time to reboot?

Are we heading into a period where the US emulates China and withholds economic data that paints it in a bad light?

Even then, their relevance is tenuous for you. After all, the US economy is not the stock market.

However, the stock market IS a forward projection of the earnings that companies can expect in it.

That will matter for your investments, as is the case with most Western economies. If America sneezes, we catch a cold.

So, what do we know in this murky period and what troubling signs are emerging?

The major concerns have been around sentiment.

Both US job and consumer sentiment are back to pandemic levels of pessimism.

Yet, looking deeper than just the surveys shows a clear sign of a split between the haves and have-nots.

‘The K-shaped economy’ has re-entered the lexicon after fading from memory, along with the COVID period that defined it in recent years.

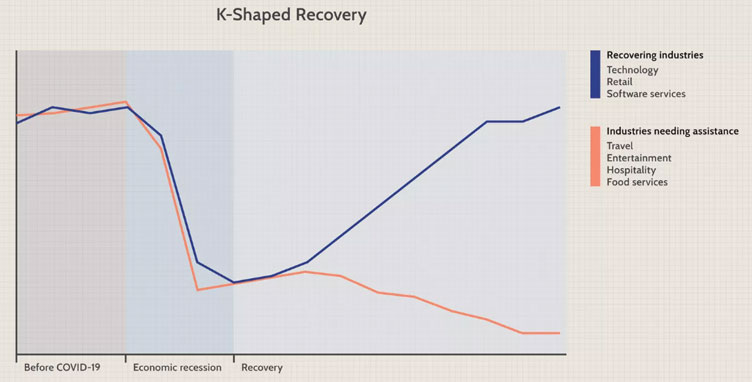

This is the idea that different economic segments clearly diverge. Some sectors experience strong growth (the upward arm of the K), while others face stagnation or decline (the downward arm).

Source: Investopedia

As the pandemic showed, the K-shaped recovery is no longer just about income brackets. It’s about which companies serve which customers, and the recent earnings season provided some indications that the divide is widening.

The Golden Arches are Cracking

McDonald’s latest quarterly earnings paint a picture of two Americas eating at the same restaurant.

Global sales rose 3.6%. US comparable sales climbed 2.4%. Sounds healthy, right?

Look closer. Total US visits actually fell 3.5% year-over-year.

CEO Chris Kempczinski laid it bare on the earnings call, saying the nation faces a ‘two-tier economy’:

‘Traffic from lower-income consumers [is] declining nearly double digits in the third quarter, a trend that’s persisted for nearly two years.’

McDonald’s is growing sales with fewer customers. The poor have left the building, while wealthier diners pick up the slack.

Coca-Cola shows the same split. Revenue rose 6%, but sales volume was flat — even down in some areas.

To keep low-income buyers, Coke is rolling out 7.5-ounce cans at US$1.29.

When you shrink the product to maintain affordability, something’s wrong. Meanwhile, their premium brands are flying off the shelves.

The same word and overarching sentiment can be seen in the earnings calls of Delta Airlines, Burger King, and Procter & Gamble.

Bifurcation… the haves and have-nots.

The 2026 Warning Bell

History doesn’t repeat, but it could rhyme with a vengeance here.

In 2007, subprime borrowers stopped paying mortgages first. By 2008, investment bankers were carrying boxes out of Lehman Brothers.

Today’s version looks different but could follow the same script. Lower-income consumers maxed out credit cards (now at record US$1.14 trillion).

We’ve already seen some of the subprime auto lenders and car parts manufacturers, such as First Brands, declare bankruptcy. Are they the canary in today’s coal mine?

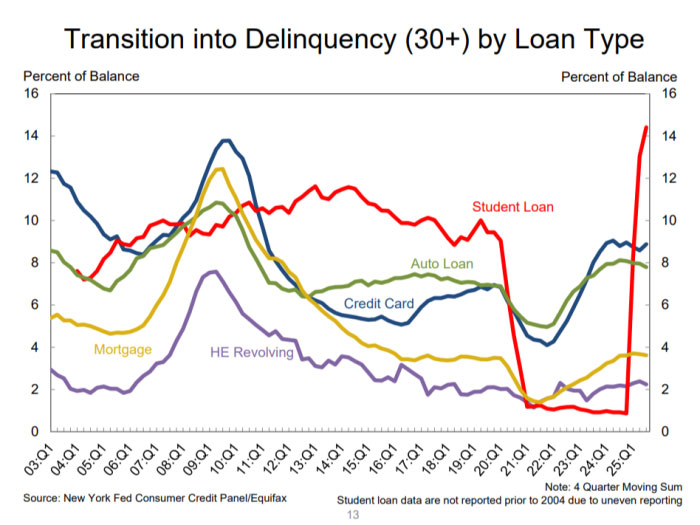

Then we have student loan debt, which is again surging after a brief period of respite under the last administration.

Source: NY Fed Consumer Credit Panel

America’s lower-income households are pulling back from McDonald’s, skipping their Cokes, and shopping only for necessities at Dollar General.

That isn’t sustainable when around 70% of your GDP comes from consumer spending.

For Australia, with our huge capital-intensive mining and trade, we are more insulated from this. We have closer to 55% of GDP from consumption, and sentiment is heading in the right direction.

The latest Westpac-Melbourne survey surprised many, jumping 12.8% to 103.8 — its first positive reading in years.

That was unexpected after September’s inflation rise to 3%, which led the RBA to hold rates.

Source: AFR – Westpac-Melbourne Institute

These are good signs for us. Perhaps we dodge the worst of the next downturn, much like the GFC.

For the US, though, things could get rocky. Companies serving these lower-income households will cut jobs next. Those cuts will spread. The contagion always moves upward.

For Australian investors who have ridden high on property and mining gains, this matters.

When U.S. consumers finally crack — rich or poor — global demand craters.

The McDonald’s indicator is flashing red.

Buffett’s US$325B cash pile and US$4T in private equity dry powder suggest they’re waiting for something.

My take? This two-track consumer economy is the calm before the storm.

The question isn’t if the arms of the K will converge — it’s whether they’ll meet going up or down.

Given that double-digit traffic declines at the world’s largest restaurant chain, I wouldn’t bet on up.

The fog Powell mentioned isn’t about missing government data.

It’s about missing the obvious signs.

Regards,

Charlie Ormond,

Small-Cap Systems and Altucher’s Investment Network Australia

Comments