During my entire life (which commenced in 1959), I have only ever known economic growth.

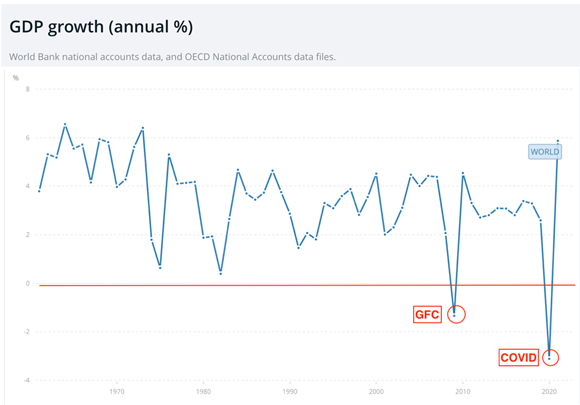

Since the early 1960s, world economic growth has averaged 3.8% per annum.

Only two years out of 60-odd years have been negative…GFC and COVID.

|

|

| Source: World Bank |

Those fortunate enough to be living in the developed world have enjoyed the lion’s share of the world’s economic bounty.

A trend spanning more than six decades pretty much becomes our accepted norm.

Individuals, businesses and governments make plans, policies and promises based on the trend continuing…indefinitely.

What has been will continue to be so.

Society has built certain expectations regarding employment opportunities, property values, retirement outcomes, education standards, security and the provision of healthcare and welfare.

Meeting those expectations (and in some cases, entitled demands) is entirely dependent upon the long-established growth trend resuming its annual 4% trajectory.

On the surface, 4% per annum seems like a reasonable number.

However, on a compound basis (using the Rule of 72) meeting that number would require the world economy to double in size every 18 years.

The math on this is daunting.

Global GDP is currently around US$100 trillion.

If trend growth was to resume, then in 2041, global GDP would be US$200 trillion. In 2059, US$400 trillion. In 2077, US$800 trillion. In 2095, US$1,600 trillion.

With population numbers having peaked in the developed and much of the developing world, where do the next big wave of credit-hungry borrowers and consumers come from?

The need for an ever-expanding base but fewer contributors…didn’t Bernie Madoff run one of those schemes?

Will the generations coming after us boomers be able to say they’ve had a lifetime of continuous growth in the decades to come?

I suspect not.

Trees don’t grow to the sky

Trees, we are told, do not grow to the sky. However, if you listen to economists and policymakers, economies apparently can go where trees cannot…to the sky and beyond.

Delivering on society’s considerable expectations has rendered the global economy and financial system hostage to growth…at any cost.

Past growth was largely a function of debt, demographics and falling interest rates.

What was, is not what’s going to be.

Debt levels are much higher.

Birth rates are much lower.

And interest rates (thanks to stubbornly high inflation) might just be in a secular (long-term) upward trend.

Future generations are facing a whole different set of circumstances to the ones my fellow boomers and I have lived through.

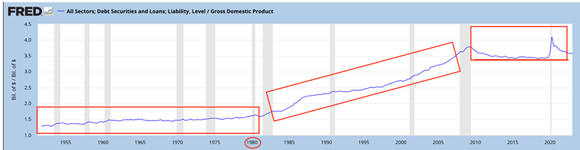

If we use the US economy as a proxy for the West, we see the past six decades of debt accumulation can be broken up into three distinct periods.

|

|

| Source: FRED |

- Post-Second World War to 1980 — the ratio of Debt to GDP was in the 1.0 to 1.5 zone.

- 1980 to 2008 — the debt to GDP ratio steadily rises (due to falling interest rates) from 1.5 to over 3.5

- 2008 to present — debt to GDP has stagnated in the 3.5 to 4.0 zone. Adding more debt (as a % of GDP) is getting more difficult…even though for most of this period interest rates were suppressed.

There’s no doubt the addition of borrowed funds was a major contributor to economic growth.

But what was once a boost is now becoming a burden.

In the period when a dollar of debt delivered a dollar of economic output, US GDP was higher. Then, as the US economy was asked to shoulder more and more debt, the pace of growth slowed.

Servicing the considerable debt obligations is taking money away from consumption.

|

|

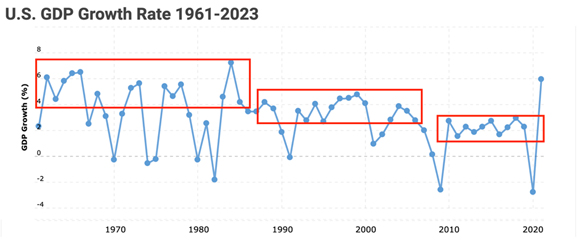

| Source: Macro Trends |

The global economy’s initial reliance on debt for growth — starting in 1980 — has become a relationship of full-blown dependency.

It is impossible for the GDP needle to move into the positive without a continued and exponential accumulation of debt.

Therein lies the problem we face.

Do we continue this path of economic self-sabotage OR take evasive action (albeit a little belatedly) to avoid a bad situation becoming worse?

Many promises will be broken

The problem for policymakers is that 2023 is not 1981.

We are not coming off a low debt base. Boomers are almost 40 years older and focused on retirement.

The highly competitive economic forces of China and India did not exist in 1981.

New-age technology and automation are transforming the world and the way we do business.

Central bankers and governments want a resumption of past growth trends…driven by the continued accumulation of debt. But which sectors are going to have the capacity to continue borrowing exponentially?

Households?

Corporates?

Well, those two sectors kind of go ‘hand-in-hand’. If households act with restraint, the corporate sector, faced with lacklustre demand, has less need to gear up.

Therefore, the burden of creating the illusion of GDP growth will fall onto governments.

Financing more and more unproductive initiatives.

But who is going to buy all this debt?

Will central banks — like the Bank of Japan have done — be the back-door financiers?

Probably. But, as Japan is now recognising, this fraud has a limited shelf life…then what?

Reality hits.

And the assumption of central bankers being the buyers of first resort assumes we still have central banks.

I can hear it now, ‘Don’t be stupid, of course there will be central banks’.

Probably, but not definitely.

When ‘The Everything Bubble’ finally busts and the wreckage caused by their idiotic policies is laid bare, central bankers will be about as popular as Donald Trump at a transgender rally.

Will political powerbrokers be able to withstand the public pressure to abandon the concept that a handful of out-of-touch academics know what’s best for us? Maybe. But I don’t rule out the possibility of the unexpected.

The easy days of lazy growth are behind us.

What lies ahead is a very rocky and treacherous road.

For my children and grandchildren, I wish it wasn’t so.

But the world we are going into is vastly different and more challenging than the one that boomers grew up in.

Things we have taken for granted — year-on-year growth, share and property markets always going up, indexed age pensions and first-world health systems — are under threat in our future.

Why so gloomy?

Simple. If something cannot continue, then it won’t.

Denying the truth of the maths won’t change the outcome.

To avoid being blindsided by what’s hiding in plain sight, be prepared for many promises to be broken.

We are at a dangerous point in the market cycle — when risks and valuations are high and fear levels are low. We’ve been here before and it does not end well.

Retention of capital should be your priority.

Sixty years of growth bestowed upon society a misguided sense of stability.

It’s timely to remember the words of famed economist Hyman Minsky, ‘stability breeds instability’.

In the coming years, I think we’re going to rediscover just how true Minsky’s words were.

Regards,

|

Vern Gowdie,

Editor, The Daily Reckoning Australia