‘Only when the tide goes out do you discover who’s been swimming naked.’

Warren Buffett

In 2017, the S&P 500 Index was up almost four-fold from its March 2009 low.

Eight years of relatively steady appreciation is rare. The Roaring Twenties bubble took around six years to inflate. The dotcom bubble was five years in the making. The US housing bubble only took a little over four years.

By historical measures, in 2017, the US market was living on borrowed time. The only thing we didn’t know was when, not if, this latest episode of exuberance and excess would end.

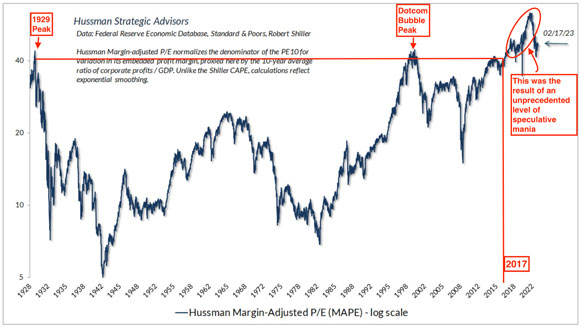

Using John Hussman’s Margin Adjusted P/E (MAPE) model as context on the value proposition offered by the S&P 500 in 2017, we can see it was a whisker below the US market’s two most infamous bubble peaks.

With hindsight, we know a never-before-seen speculative mania gripped market participants and took overvaluation to a whole new level.

|

|

| Source: Hussman Strategic Advisors |

The reason for highlighting 2017? This was the year I wrote How Much Bull can Investors Bear?.

Concerned we were on the cusp of yet another capital-destroying moment, the book was my way of trying to alert people to the dangers of the myths the industry perpetuates in the UP phase of the cycle.

Unfortunately, the longer a market stays on the UP, the easier it is to dismiss calls for caution as the ramblings of ‘the boy who cried wolf’.

In reality, the more a market rises, the more dangerous it becomes, and the more investors should heed the advice to act with restraint.

History is littered with stories of those who have said after the event, ‘if only I had known’.

For the greater good of society, the bubble should have busted in 2017.

Far less damage would have been done.

And a lot less people would have been able to make obscene amounts of money at the expense of the many.

The tide is going out, the ARK has run aground

On 9 March 2023, the Financial Times published this article:

|

|

| Source: FT |

Here’s an edited extract from the article (emphasis added):

‘Cathie Wood’s Ark Investment Management has earned more than $300mn in fees on its flagship exchange traded fund since its inception nine years ago, while wiping out almost $10bn of investors’ cash in the same period.

‘This year it has brought in an average of roughly $230,000 in fees a day as ARKK’s value recovered slightly, rising by a quarter. “Investment fees have provided ARK and Cathie Wood a very good living,” said Elisabeth Kashner, director of global funds, research and analytics at FactSet. “Her investors haven’t been so lucky.”’

Chapter six in How Much Bull Investors Can Bear? is titled ‘Passive versus Active Management — The Tortoise and the Hare’.

If we compare the performance of Cathie’s actively managed ARKK (since the fund’s inception) with the passive Invesco QQQ (an exchange-traded fund that tracks the Nasdaq-100 Index with an expense ratio of just 0.2% per annum), we can see in the UP phase of the cycle, ARKK floats a lot higher in 2020 after the Fed pumped massive amounts of liquidity into the system:

|

|

| Source: Yahoo! Finance |

Then, the inevitable happens. Out-performance on this scale cannot be maintained. But during the boom, investors flock in on the belief it can and will continue to disconnect forever and a day. No amount of warning can stop the lemmings.

As boom turns to bust, Cathie’s ARKK has run aground.

The tortoise (the low-fee index fund) has outperformed AND please take note of this, the BUST is only in its infancy. The real downside action is yet to come.

The tide is going out and Cathie is swimming naked.

But with US$300 million in fees, I’m pretty sure she’ll be able to buy herself a fine pair of bathers…not so sure about her investors though.

As an added extra for today’s Daily Reckoning Australia, here’s what I what I wrote in 2017 about hedge funds in chapter six of How Much Bull Investors Can Bear?…it was as true then as it is today. The cycle ALWAYS repeats:

‘The psychology of winners and losers

‘Understanding, or at least appreciating, the game that goes on between our ears is crucial to improving the odds of being classified as a “successful long-term investor”.

‘Get to know the inner you…the one you’ll be fighting against.

‘Our thought processes control our emotions and actions. We choose (consciously or subconsciously) to act rationally or irrationally to circumstances based on emotion. Which is why it’s often suggested you count to 10 before doing anything.

‘Here are a couple of psychological conditions that relate to investing:

- ‘Metacognition: The less competent you are at a task, the more likely you are to overestimate your ability to accomplish it well. Competence in a given field actually weakens self-confidence.

- ‘Dunning-Kruger effect: Dunning-Kruger is a cognitive bias in which unskilled people make poor decisions and reach erroneous conclusions, but their incompetence denies them the metacognitive ability to recognise these mistakes.

‘Starting my career in financial planning in 1986 (with negligible investment experience), I felt the pressure to “know it all”; if I didn’t, then clients would perceive me as incompetent. A classic case of metacognition.

‘Years of being chewed up and spat out by the market taught me a great deal about humility, and my own limitations. On balance, these experiences have made me more competent and definitely more cautious (weakened self-confidence). Even though I’m much older and wiser than I was in 1986, I continually question and re-assess my assumptions.

‘In 1984, Bennett W Goodspeed wrote “The Tao Jones Averages: A Guide to Whole-Brained Investing”.

‘The Tao reference in the title relates to the Taoist philosophy of “balance”.

‘A topic Goodspeed discussed was the power of the “articulate incompetent” to influence public thinking (there are a few politicians that fit this category).

‘Goodspeed identified the following characteristics of the “articulate incompetents” in the investing world:

- ‘The more self-confident an expert appears, the more likely TV viewers will believe them…but the worse their track record is likely to be.

- ‘So-called expert forecasters do no better than the average member of the public.

- ‘Forecasters who predict a single outlier correctly are more likely to underperform the rest of the time.

‘Whereas:

- ‘Experts who acknowledge that the future is inherently unknowable and unpredictable are perceived as being uncertain and, ironically, less trustworthy.

‘The takeaway from these observations is that the majority want to be led, even if the charismatic but clueless leader is taking them down the road to ruin. The faces of a few central bankers, professional managers and CEOs I have known come to mind as I write this.

‘Apparently, most people do not want qualified, cautious advice — and definitely want no part of “boring”.

‘The purpose of providing a historical perspective and psychological profiling is to explain why, through the centuries, we can be our own worst enemies when it comes to investing.

‘Ignorance. Gullibility. Overconfidence. Greed. Fear. All of these play a role in producing poor outcomes.

‘Knowing and accepting the contribution these factors make to investment failure is half the battle. The other half is having a disciplined strategy to minimise the risk of falling off the wagon and being caught up in the social mood created by the next crisis or bubble.

‘And throughout the battle you have to understand industry spin.

‘The investment industry knows investor psychology better than anyone. Which is precisely why they design the products the way they do…with lots of promise.

‘The industry goes to great lengths to make investments sound “sexy and alluring” — using terms like “absolute return funds”, “tax effective”, “alternative investments”, “private equity”, “special opportunities” and so on.

‘Sexy sells. And in the investment business, the very highly-priced hedge funds are definitely portrayed as sexy.

‘Hedge funds are perceived as the masters of the investment universe. These funds (apparently) employ only the best and brightest individuals who take positions that are designed to outperform the market…irrespective of whether it is rising or falling.

‘Absolute returns (no negative results over a stipulated period of time) are another promise offered by some hedge funds.

‘If the aura of hedge funds makes them sound too good to be true, it’s because, in reality, most are.

‘Unfortunately, far too many investors fail to apply this cynical approach and actually believe the “hype” — as we know they are wired to do.

‘When the founder of the world’s largest hedge fund, Ray Dalio, was asked, “How many hedge funds are worth investing in?”, his response was, “There are about 8,000 planes in the air and 100 really good pilots.”

‘Many a true word is said in jest.

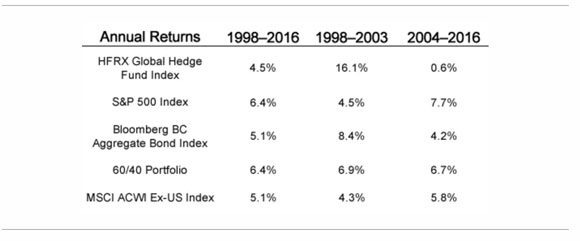

‘The following table compares the annual performance of the HFRX Global Hedge Fund Index (since 1998) to other benchmarks…

|

|

| Source: Enterprising Investor |

‘Over the longer term — 1998 to 2016 — the Hedge Fund Index has slightly underperformed.

‘However, when you take the 1998-2003 performance away from the hedge funds, they have produced dismal performance since 2004.

‘Initially, the small and nimble hedge fund players did add significant value for their excessive fee structure — a 2% annual management fee plus a performance fee of 20% on gains achieved above a base return, or “hurdle” rate.

‘The late phase of the dotcom boom in the 1990s provided the hedge fund industry with a lot of low-hanging fruit to profit from. The obscene amounts of fees extracted from the hedge fund pioneers resulted in nearly every man and his dog hanging out their hedge fund shingle. The result of this overcrowding in the hedge fund marketplace is demonstrated in the post-2004 performance of this sector.

‘With so many managers looking to get on the fee gravy train, it means the small universe of undervalued investment opportunities is well and truly trawled over by the hedge fund herd.

‘Since 2004, the hedge fund average has seriously under-performed the S&P 500.

‘However, as the hedge funds, in recent years, have outperformed the cash rate (a measly 0.25%), some have still been able to pay themselves their performance fee (in addition to the annual management fee).

‘Industry insider Simon Lack shone the light on the inequity of the hedge fund fee structure in his 2011 book The Hedge Fund Mirage:

- ‘From 1998–2010, hedge fund managers earned $379 billion in fees. Over the same period, the investors in their funds earned only $70 billion in gains.

- ‘Managers retained 84% of investment profits while the investors, who put up the capital, received a paltry 16%.

- ‘To make matters worse, up to one-third of the hedge funds are only accessible via feeder funds or a fund of funds approach. This adds a further layer of administration fees to be absorbed by investors. Simon Lack estimates the additional administration fees are approximately $61 billion. When you account for the additional fees, investors actually received $9 billion ($70 billion less $61 billion), and the industry raked in $440 billion ($379 billion plus $61 billion). The final split: hedge funds 98% and investors 2%.

‘Despite what you may have been led to believe, hedge funds are not in the investment business. They are in the fee-capturing business.

‘Sure, some hedge funds are worth their weight in gold. But which ones?

‘Picking the outperformer in advance is random luck, and failure to do so (which is where the majority end up) comes with a hefty price tag.

‘In classic “don’t let the facts get in the way of a good story” tradition, the industry knows that, when it comes to sexy versus matronly, investors are wired for the former.’

Regards,

|

Vern Gowdie,

Editor, The Daily Reckoning Australia