There are few materials subjected to such heated debate as uranium.

While the 2011 Fukushima disaster has crippled demand for uranium over the past 10 years, the market is showing signs of a resurgence.

But why now?

Advocates have often touted nuclear energy as a game-changing tool in the fight against climate change.

But that hasn’t been enough to see nuclear prices rise from levels that have pushed away marginal producers in recent years.

So why is now different?

Growing concerns over the destructive effects of climate change and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine have quickened the world’s transition to cleaner energy.

The European energy crisis that hit its peak between September 2021 and July 2022 saw gas prices rise to eight times their 10-year average and forced drastic government policies to curb the impact of rising prices on households and businesses.

Energy prices have fallen since those crisis points, but renewed concerns about tightened supply and the end of some government protections have meant prices are climbing again.

Take the United Kingdom, for example. The UK spent $37.9 billion (1.4% of GDP) to cap household energy spending at around 11% of household spending.

The graph below shows how bad it got for the UK, which was pressured into responding with an ‘energy price guarantee’ that capped household energy costs.

That cap ended on 30 June 2023, and since then, we have seen pressures on the price return as gas prices begin to rise again.

It’s a similar situation in Germany

Germany has been the poster child for a renewable-driven economy for a long time. They’ve very advanced plans to have an 80% renewables grid by 2030.

But this plan is now coming apart at the seams.

Because of it, they’ve gone from being the powerhouse economy of Europe to being dubbed the new ‘sick man’.

As CNBC reported on 4 September:

‘The “sick man of Europe” moniker has resurfaced in recent weeks as manufacturing output continues to stutter in the region’s largest economy and the country grapples with high energy prices.

As national broadcaster Deutsche Welle reported, the problems Germany is facing are complex:

‘Germany wants out of fossil fuels: no coal, no gas, no nuclear power plants. Instead, the country wants to commit fully to renewables.

‘But does this bring with it the threat of a major power blackout? Germany is gradually realising where the sticking points are.

‘Take grid security: This is much easier to guarantee in a power network with just a few dozen large power stations than in a decentralised network with multiple small-scale electricity producers such as rooftops with solar panels or wind turbines.

‘“It’s now a matter of having to intervene several times almost every day to guarantee grid security,” says the spokesperson for one major network operator. If grid security can no longer be maintained, the threat of a nationwide blackout suddenly becomes very real.

‘Another problem is reliability. Because the sun doesn’t always shine and the wind doesn’t always blow, there might be too little power available on particular days and at particular times of the year. This also raises the possibility of unforeseen power failures.

‘One potential remedy could be power storage. There are many different ideas about how to securely store energy in order to bridge power gaps in the renewables’ supply: pumped-storage power plants, hydrogen storage, gigantic batteries.

‘But, if these technologies exist at all, they do so only on a very small scale: Current storage capacity in Germany is 40 gigawatt hours — enough to supply the country for up to 60 minutes. And if there’s still no wind and the sun still isn’t shining…?’

With more countries recognising the limitations of relying solely on renewable energy in the near future, it becomes imperative to explore other options.

This raises the question of how uranium will fit into the larger picture of the global economy and what impact it might have on uranium stocks.

First, let’s cover the basics of uranium before delving deeper into the future of nuclear energy.

Navigate to a section quickly:

- Uranium prices: boom and bust

- What is uranium?

- Where do we find uranium?

- What are the common uses of uranium?

- Is nuclear energy clean?

- Is nuclear energy safe?

- Five promising uranium stocks on the ASX

- Benefits of investing in uranium stocks

- Risks of uranium stocks

- Conclusion: investing in uranium stocks

Uranium prices: boom and bust

‘The civilian nuclear industry is poised for world-wide expansion. Rapidly growing demand for electricity, the uncertainty of natural gas supply and price, soaring prices for oil, concern for air pollution and the immense challenge of lowering greenhouse emissions, are all driving a fresh look at nuclear power.

‘At the same time, fading memories of Three Mile Island and Chernobyl is increasing confidence in the safety of new reactor designs. So the prospect, after a long hiatus, of new nuclear power construction is real, with new interest stirring in countries throughout the world.’

The above is a quote from Lance Joseph, former Australian Governor on the board of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA).

Mr Joseph’s quote is highly representative of the current market conditions surrounding nuclear.

Yet, he made this comment all the way back in 2006.

The freshness of his views highlights the drawn out and volatile process of nuclear adoption.

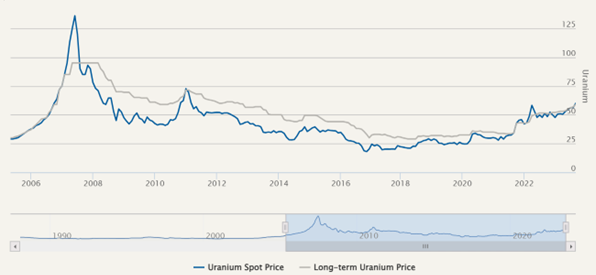

Soon after those 2006 comments, the uranium market experienced an exponential boom…followed by a hard bust.

Uranium prices crashed in 2007, and any market recovery a few years later was halted by the tragic Fukushima nuclear disaster.

For years since, uranium prices were in the doldrums…but they’re on the uptick once more:

Source: Australian Financial Review

What is uranium?

Uranium is a naturally occurring radioactive material and one of the heaviest elements. It’s a very dense silvery white metal — 1.7-times denser than lead — and one of the heaviest elements. Most importantly, it’s the key feedstock for nuclear energy.

Uranium was first discovered by German chemist Martin Klaproth in 1789, as a part of a mineral fittingly called ‘uraninite’.

However, it would be another 50 years before a French chemist would isolate uranium as a metal.

Then it would take another 50 years before French physicist Henri Becquerel would realise uranium has radioactive properties.

Finally, our journey of discovering the full potential of uranium would finish just before the Second World War. In 1938, two German physicists proved that it’s possible to split uranium into parts, releasing energy in the process.

Fast-forward to today, and the science gets a bit more complicated.

Today, we know there are three different uranium isotopes that occur naturally:

- U-238 makes up 99.28% of uranium, has a half-life close to the age of the Earth.

- U-235, which contains the most energy and makes up about 0.7% of uranium.

- U-234 is found in trace amounts (less than 0.0055%).

Only U-235 can be the basis of a nuclear reaction, while U-238 has no use in nuclear energy production. However, some newer technologies may yet turn this into a non-nuclear, but valuable fuel source.

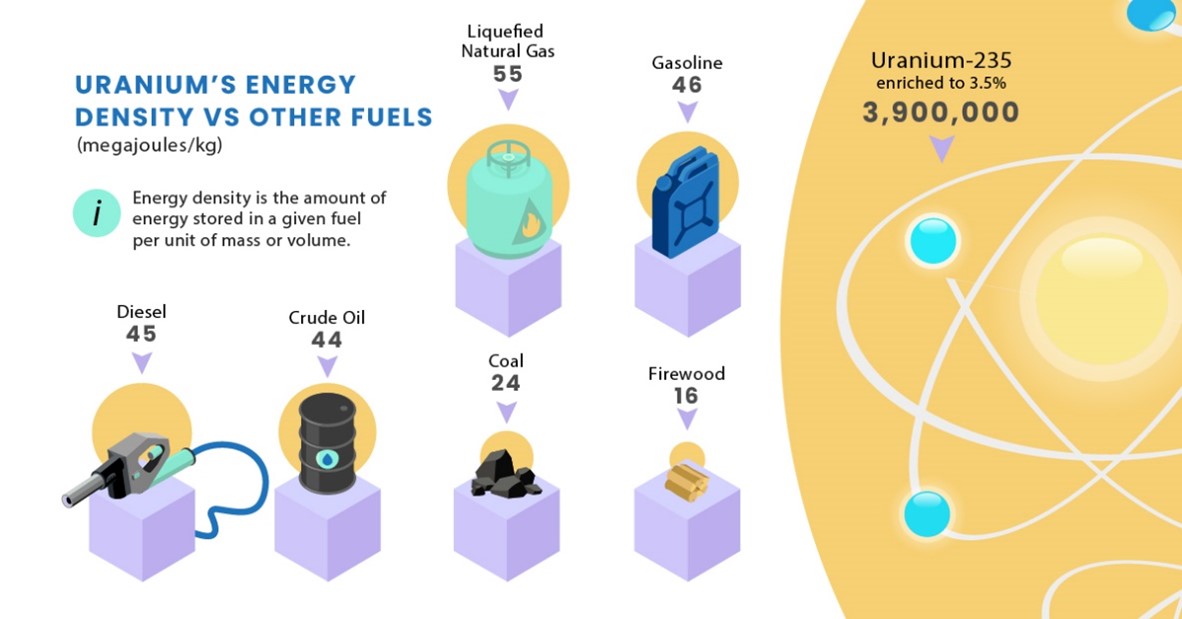

As a fuel source, it is incredibly energy dense. One uranium pellet the size of your fingertip has as much energy as; 1 ton of coal, or 149 gallons of oil, or 17,000 cubic feet of natural gas.

Where do we find uranium?

Uranium is found in minerals like pitchblende, uraninite, and brannerite. You can also find uranium in substances like phosphate rock deposits and minerals like lignite.

Importantly, uranium is 500-times more abundant in the Earth’s crust than materials like gold.

It’s as common as tin.

But while uranium can be found almost anywhere, only a few places in the world have economical concentrations of uranium ore.

Concentrations of uranium that are economic to mine — a key consideration when assessing the market for uranium — occur in about a dozen different deposit types in a range of geological settings.

According to the Uranium Information Centre, a typical concentration of uranium in high-grade uranium ore is 20,000 ppm, or 2% uranium.

Low-grade ores are 1,000 ppm, or 0.1% uranium.

One of the most famous uranium ore deposits is the Shinkolobwe mine in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

It played a crucial role in supplying the US with uranium for its Manhattan Project.

Shinkolobwe’s ore grade was extremely high. As a BBC profile reported:

‘Mines in the US and Canada were considered a “good” prospect if they could yield ore with 0.03% uranium. At Shinkolobwe, ores typically yielded 65% uranium. The waste pile of rock deemed too poor quality to bother processing, known as tailings, contained 20% uranium.’

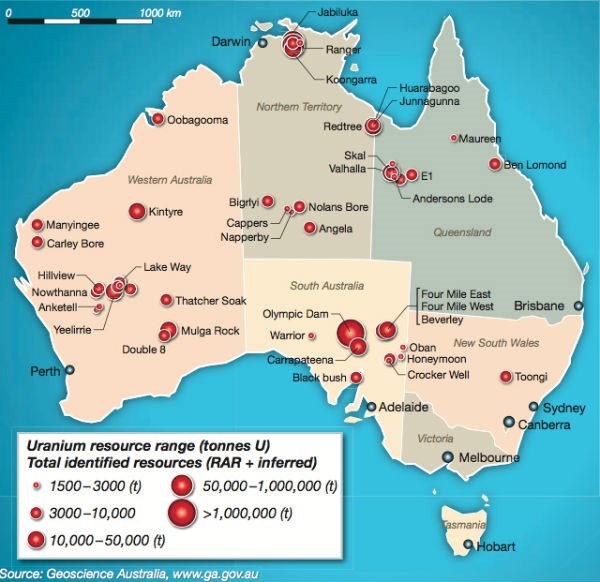

While Australia is known for its reserves of iron ore and coal, the country is also sitting on the world’s largest-known uranium resource.

Australia is home to almost one-third of the world’s total uranium resource:

Source: Nuclear Engineering International

While Australia has bountiful uranium resources, it’s not the world’s largest producer.

In 2022, Kazakhstan produced the largest share of uranium from mines, with 43% of world supply which totalled 21,227 million tonnes (Mt).

Canada was second with 15% at 7,351Mt, while Nambia was third at 11% with 5,613 Mt.

According to the World Nuclear Association, in 2022, the largest 10 companies by production contributed about 94% of the world’s uranium production.

Source: World Nuclear Association

What are the common uses of uranium?

Before the Second World War, society had little use for uranium.

The element was used as a chemical catalyst in a limited number of specific applications, simple things like colouring ceramics.

Now, uranium has two major (peaceful) purposes: as fuel in nuclear power reactors to generate electricity, and for the manufacture of radioisotopes for medical and applications.

Uranium also has a darker history for its association with atomic bombs.

As the BBC reported:

‘It was only when nuclear fission was discovered in 1938 that the potential of uranium became apparent.

‘After hearing about the discovery, Albert Einstein immediately wrote to US president Franklin D Roosevelt, advising him that the element could be used to generate a colossal amount of energy — even to construct powerful bombs.

‘In 1942, US military strategists decided to buy as much uranium as they could to pursue what became known as the Manhattan Project.’

Power generation

Here in Australia, it’s worth noting that locally produced uranium is exclusively exported for peaceful purposes — after all, uranium is still necessary for around 9% of the world’s electricity generation.

And as fossil fuels are slowly phased out, that number may grow.

More countries are considering nuclear energy as a viable alternative to fossil fuels.

Compared to traditional power sources, nuclear energy comes with relative reliability, lower greenhouse emissions, and fewer operating costs.

Increasing demand for nuclear energy is the primary driver for most mineral exploration companies producing uranium in Australia.

Radioactive isotopes

While uranium is most commonly associated with power generation and nuclear weapons, the element does have other applications.

For instance, treated uranium is a vital component in the production of radioisotopes — radioactive isotopes that have a vital role in the food and medical processing industries.

Over the past decade, the radioactive isotope market has experienced tremendous growth. By 2027, the medical radioisotope market cap is expected to reach around US$37 billion.

Right now, North America is the dominant region when it comes to diagnostic radioisotopes, owning around half of the current market, with Europe being a distant second at 20%.

But what exactly are radioactive isotopes used for?

These isotopes are vital for the fast-growing field of nuclear medicine — an exciting direction in medical imaging that takes minuscule amounts of radioactive matter and uses it to determine and treat various diseases and conditions.

Right now, radioisotopes are vital for the diagnosis, detection, and treatment of everything from heart conditions and cancers to endocrine, gastrointestinal, and neurological issues.

They can also be applied in the food processing industry. The isotopes’ role is to remove harmful bacteria that would otherwise be present in food matter. This process extends a myriad of food products’ shelf life.

The World Health Organisation and various other international bodies have determined that this process (commonly referred to as food irradiation) is a more effective and safer alternative to most heat and chemical treatments.

In the past, uranium was also used for the production of lamp filaments, smoke detectors, and dyes and stains for leather and wood.

Is nuclear energy clean?

Plenty of experts say that uranium is a preferable choice over fossil fuels, especially coal as it’s a cleaner and safer alternative to fossil fuels.

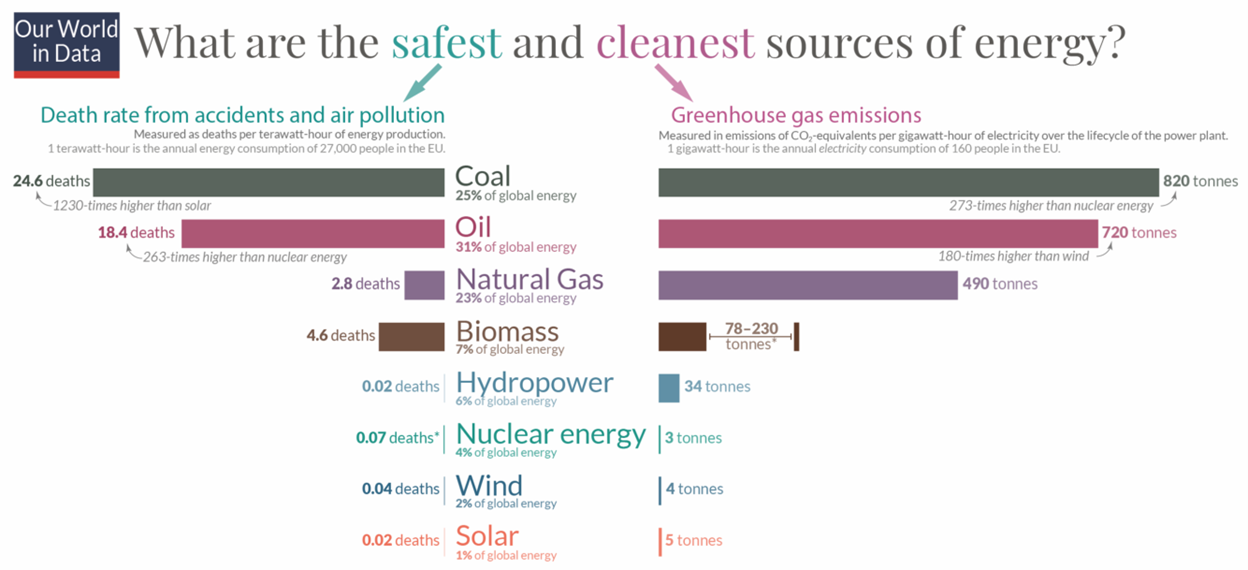

Consider the following excerpt from Oxford University’s Our World in Data report on nuclear:

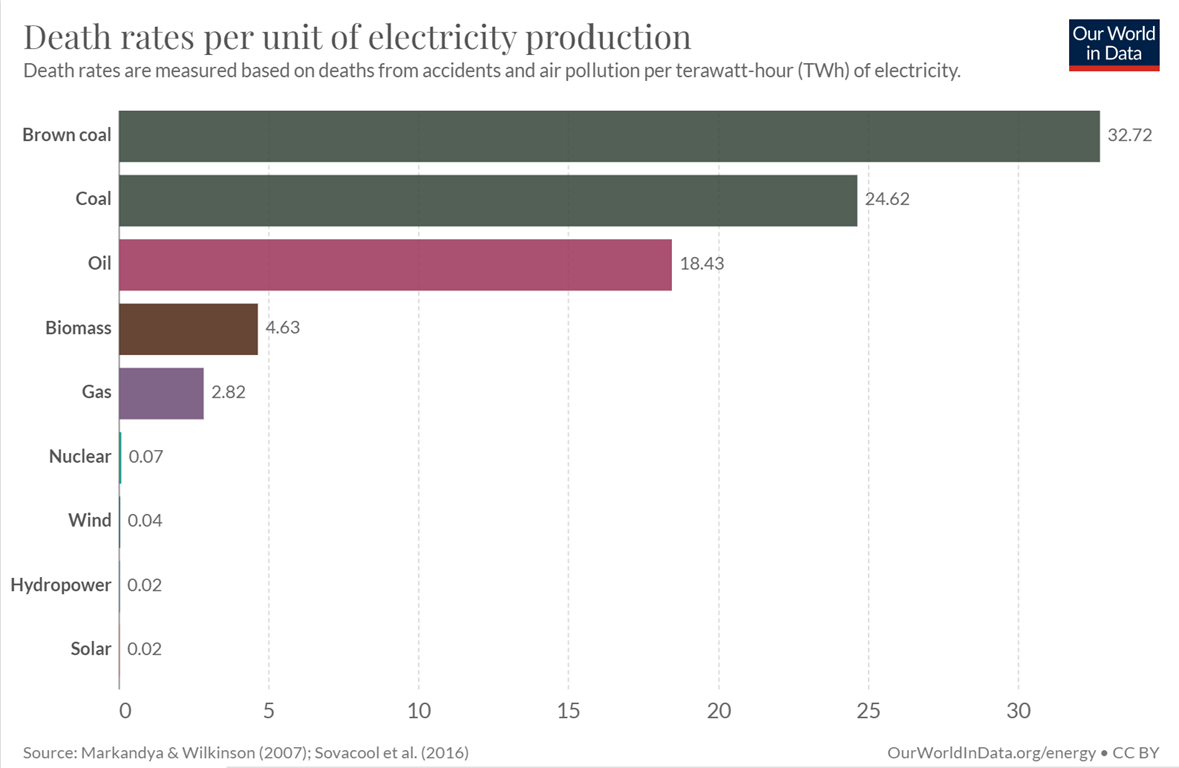

‘The world is not facing a trade-off — the safer energy sources are also the least polluting. We see this from the symmetry of the chart.

‘Coal causes most harm on both metrics: it has severe health costs in the form of air pollution and accidents, and emits large quantities of greenhouse gas emissions.

‘Oil, then gas, are better than coal, but are still much worse than nuclear and renewables on both counts.

‘Nuclear, wind, hydropower and solar energy fall to the bottom of the chart on both metrics. They are all much safer in terms of accidents and air pollution and they are low-carbon options.’

Nuclear power plants don’t emit emissions while they generate power, and only very small amounts during uranium’s production cycle.

On the other hand, other sources of electricity generate much higher greenhouse gas emissions.

Unlike fossil fuels, nuclear power plants don’t emit any toxic gases, mercury, sulphur dioxide, or carbon dioxide.

Source: Our World in Data

Is nuclear energy safe?

Nuclear energy is often considered by many as unsafe, volatile, and susceptible to catastrophic accidents.

Take this Greenpeace article from 2021 on nuclear energy, which concluded:

‘Nuclear energy has no place in a safe, clean, sustainable future. It is more important than ever that we steer away from false solutions and leave nuclear power in the past.’

How does nuclear’s safety record stack up?

Consider the chart below from Oxford University’s Our World in Data, which shows that death rates per unit of electricity production from nuclear are lower than coal, oil, and gas:

Source: Our World in Data

As Our World in Data explained:

‘Nuclear energy, for example, results in 99.8% fewer deaths than brown coal; 99.7% fewer than coal; 99.6% fewer than oil; and 97.5% fewer than gas.

Five Promising Uranium stocks on the ASX

Before we delve into uranium companies on the ASX, it’s worth pointing out that uranium stocks are commodity stocks — exposed to the cycle of their underlying commodity.

Whether or not a uranium miner is highly efficient and cost-effective, it will still depend heavily on the wider uranium market and the prevailing uranium price.

Now, here are some ASX uranium stocks.

Paladin Energy [ASX:PDN]

Paladin Energy has the biggest market capitalisation of all ASX uranium stocks, though, it’s also had its fair share of troubles since the post-2011 price slump.

In mid-2018, the company decided to mothball its huge Namibia-based uranium mine, Langer Heinrich. Paladin Energy had to place it in maintenance and care because of the continued global spot price drops of uranium.

But since then, world market conditions have improved, which is why Paladin launched a $200 million equity raising for a mine restart.

After the formal restart project was launched in July 2022, PDN was able to target commercial uranium production at Langer Heinrich — which is due to officially commence in CY24.

The company now stands on the edge of breaking even with some analysts forecasting profits of nearly $50 million by 2024 so this could be one to watch.

Lotus Resources [ASX:LOT]

Having once produced over 1,500 tons of uranium annually, Lotus Resources is one of the only ASX listed companies mining uranium in the African nation of Malawi.

Its golden goose, the Kayelekera mining field had been shut down from 2014 due to low uranium prices, but as the commodity surged, Lotus decided to recommission the facility.

The project is unfortunately still in limbo due to delays on the recommission but things may turn around soon with recent meetings with the Malawi government looking positive before the company makes its final investment decision.

The company has also announced a post quarter end merger with A-Cap Resources [ASX:ACB] which holds a considerable uranium project in Botswana.

The merger will create a leading Southern African-focused uranium player that should see synergistic cost savings and be more attractive to offtake partners.

The merged group will have a combined resource of 241 Mlbs that could see them hold the third largest attributable resource in the market.

Boss Resources [ASX:BOE]

In June 2022, Boss Resources made a final investment decision to develop the Honeymoon uranium project.

Since then, the project has been running on time and on budget with $103 million cash in hand and a strategic stockpile of uranium valued at over $100 million based on current

The South Australian project is now fully-funded and BOE expects production to re-start in the December quarter of 2023.

An enhanced feasibility study commissioned by BOE found that the Honeymoon project can be ‘economically robust’:

- ‘Honeymoon is economically robust with an IRR of 47% at a US$60/lb U308 price;

- ‘Honeymoon is technically robust, with nameplate production of up to 3.3Mlb U308 per annum at an AISC of US$25.62 over the Life of Mine;

- ‘Potential to extend beyond initial 11-year mine life through near mine satellite deposits.’

So while this is a pre-operational minier pick, it is definitely one you want to put on your watchlist to participate in the early stages of the new uranium bull market.

Deep Yellow [ASX:DYL]

Deep Yellow is the fourth-biggest Australian uranium explorer.

Unlike most of the market players we’ve mentioned above, Deep Yellow is mostly concerned with its three assets in Namibia:

- The non-active joint venture called ‘Yellow Dune’…

- Its active Nova joint venture, and…

- The main active project called ‘Reptile’.

Mid last year Deep Yellow merged with Vimy to create a giant in the uranium world, with two mines near development ready and geographically diverse assets the company now sits in a commanding position with Australian and Nambian assets

The merged company now holds the largest uranium resource of any ASX-listed company at 401Mlb.

As for its assets, they remain on track while the company holds no debt and $48.8 million in cash.

The Nambian Tumas Project definitive feasibility study has been complete and the company expects its final investment decision by mid-2024.

While the Australian Mulga Rock Project in WA is conducting test work and is expecting a post-acquisition definitive feasibility study to commence in CY2024.

Bannerman Resources [ASX:BMN]

The fifth-biggest uranium stock is Bannerman Energy Resources. Bannerman possesses a 95% majority of the Etango project.

This is another Namibian location, and a significant one at that — it’s the biggest undeveloped uranium deposit in the world, found in the Erongo mining region.

There are a number of other uranium mines in the same area, such as Husab (owned by China General Nuclear), Heinrich (operated by Paladin Energy), and the Rio Tinto project named ‘Rössing’.

The mine has gained it’s licencing to mine and received environmental clearance. With the definitive feasibility study completed the company expects the final investment decision during 1H CY2024.

From there construction is expected to take approximately 34 months.

In future, the Etango project might be expanded to other resources that are within the company’s trucking distance.

Benefits of investing in uranium stocks

The world is shifting to cleaner energy.

Fossil fuels are slowly being phased out.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 only hastened a process that began years ago.

Renewables are the world’s energy future. The question is what that renewables future looks like, and how big a role nuclear will play.

Clearly, as we’ve covered above, nuclear energy is one of the cleanest and safest means of energy generation.

If the politics of nuclear can be overcome, demand for nuclear — and its uranium feedstock — will likely soar.

For instance, the International Energy Agency declared that current nuclear power capacities will have to be doubled by 2050 if we’re going to meet global targets.

If nuclear energy becomes a major part of the world’s clean energy mix, then uranium can become one of the world’s biggest commodities.

Risks of uranium stocks

While global sentiment toward nuclear energy may become more favourable as the world speeds up its transition from fossil fuels, the politics of nuclear energy are an important risk factor to consider.

For instance, the 2011 Fukushima disaster caused Japan to close most of its nuclear power plants.

What followed was a decade-long bear market.

The politics of nuclear energy is fraught…and can impact the demand for uranium.

Consider the following illustration from the World Nuclear Association:

‘However, following the tsunami which killed 19,000 people and which triggered the Fukushima nuclear accident (which killed no-one) in March 2011, public sentiment shifted markedly so that there were widespread public protests calling for nuclear power to be abandoned.

‘The balance between this populist sentiment and the continuation of reliable and affordable electricity supplies is being worked out politically.

‘The government’s stated aim is for nuclear power to provide 20-22% of electricity by 2030. Earlier in 2011, nuclear energy had accounted for almost 30% of the country’s total electricity production (29% in 2009).’

Japan isn’t the only country worried about the dangers of nuclear power.

Germany has also been phasing out its nuclear energy generation from 2011.

Only three nuclear power plants remained active in Germany until recently — down from 17 in 2011 — with all three decommissioned at the end of 2022.

The politics of managing the public’s fear in Germany echoes Japan’s situation.

As a Politico report on Germany’s nuclear phase out explained:

‘In Germany, “nuclear energy has always been associated with war,” said Miranda Schreurs, a professor of climate and energy politics at the Technical University of Munich. “Whether that’s the atomic bombs in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, or Germany’s own search for nuclear capacities during World War II, and also because of the Cold War situation in Germany.”

‘That created a groundswell of opposition long before Chernobyl and the Greens’ foundation. But the 1986 Soviet-era accident turbocharged the anti-nuclear movement.

‘“That’s a memory that stays with people, if you remember that you can’t let your children play outside because you’re scared of radioactivity,” said Schreurs. “And the government always made the argument, well, that was the Soviet Union, their technology wasn’t as sophisticated as ours. But then Fukushima happened.”’

The future of nuclear energy and, with it, uranium’s price, depends heavily on not just the world’s shift from fossil fuels to clean energy, but also on the world’s sentiment towards nuclear and a reckoning with its past.

Conclusion: investing in uranium stocks

Surging commodity prices and rampant inflation created a watershed moment for the world.

Many countries faced inflation levels not seen in decades.

And energy was one of the biggest drivers of high inflation, exacerbated by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Clearly, the world is in need of an energy solution.

The global dependence on fossil fuels is waning as the world rushes to cleaner and more independent sources of energy.

Now, more than ever, energy is both an environmental and a political concern.

Nuclear energy can be a big part of the world’s energy solution.

As the World Nuclear Association wrote:

‘Almost all reports on future energy supply from major organizations suggest an expanded role for nuclear power is required, alongside growth in other forms of low-carbon power generation, to create a sustainable future energy system.’

And Australia, with its vast uranium resources, can become a pivotal global player…

Meaning that Australian uranium stocks could take centre stage in the world’s clean energy transition.

Of course, there are plenty of risks involved, and we covered some earlier.

Uranium stocks are commodity stocks…and must answer to the commodity cycle of their underlying commodity.

In this case, the commodity in question is also a contested political hot potato.

Any investment analysis of uranium stocks must account for political risks associated with nuclear energy adoption.